[ad_1]

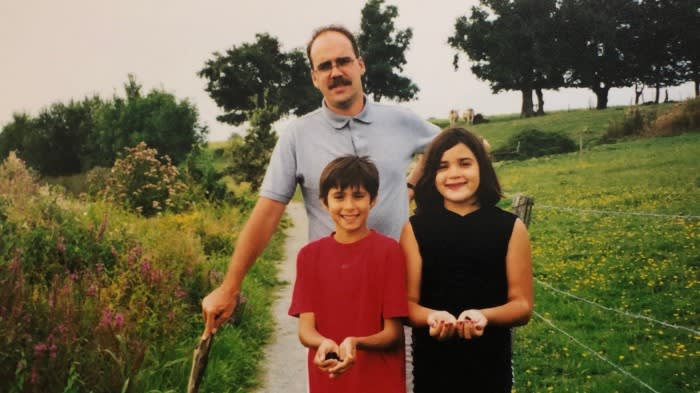

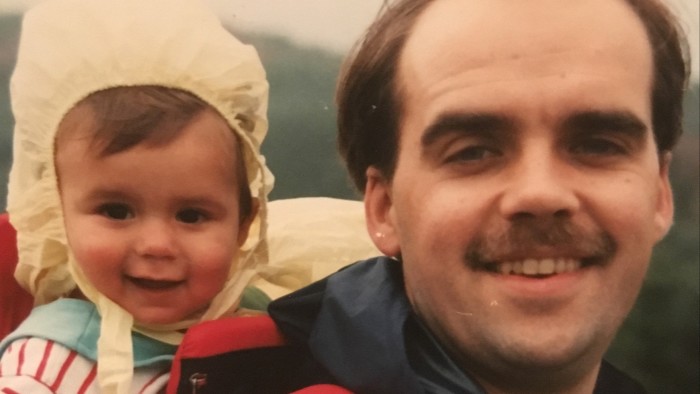

Ian Douglas took his own life the day before his 60th birthday in February 2019.

When he died he was in the terminal stage of multiple sclerosis, a disease that had left him severely disabled, confined to a wheelchair and suffering immense pain. His death was a result of a lethal dose of powerful opioids purchased on the dark web.

“I have lived with MS for over 30 years and am now reduced to a bare minimum of physical function”, the former financial analyst wrote in his final note, which his family shared with the FT.

“I would like to have to put on record that had we [had] more sympathetic assisted-dying laws in this country, in all probability I would still be alive today,” he added.

A decision not to administer treatment or to end treatment for a disease is lawful in the UK. But to help someone die is not, and carries a maximum prison sentence of 14 years.

Ian’s son, Anil, believes the law “failed” his father. It “meant he had to choose a dangerous, unpredictable and lonely way to end his life”, he said. “The law meant we couldn’t say goodbye.”

Across the UK there is growing momentum behind attempts to change the law, with politicians in the Isle of Man, Jersey and Scotland all considering the introduction of legislation to allow assisted dying.

Last month Britain’s main opposition leader, Sir Keir Starmer, pledged to give MPs a free vote on whether to legalise assisted dying in England if his Labour party wins the UK general election expected later this year.

Prime Minister Rishi Sunak said in February that “if parliament decided that it wanted to change the law”, his Conservative government would “facilitate doing that in a way that was legally effective”.

A growing number of countries are also considering whether to amend their rules. French President Emmanuel Macron has said his government will propose a draft law that would create a “right to die” for adults with incurable diseases under strict conditions.

If the law is finalised, France will join European countries including Switzerland, the Netherlands and Belgium, as well as several US states, Canada, Australia and New Zealand in giving terminally ill people the choice to die.

“There seems to be a global momentum towards more permissive legal approaches in a wide range of different countries,” said Dominic Wilkinson, professor of medical ethics at Oxford university.

“One reason for this change is that the countries’ constitutions are becoming less systematically religious and the role of religion in public policy has become less significant,” he added.

MPs in England voted against changing the law on assisted suicide — which the NHS defines as “deliberately assisting a person to kill themselves” — when a bill was debated in the House of Commons in 2015.

But Kit Malthouse, a former Conservative minister and co-chair of the all-party parliamentary group for choice at the end of life, last year said “sentiment in parliament has moved significantly” and was “getting towards a majority” in favour of changing the law to permit assisted dying.

According to a poll published last month by Opinium on behalf of the campaign group Dignity in Dying, 75 per cent of people living in the UK support assisted dying.

“The public have been way ahead of politicians for years and we are now catching up,” said MSP Liam McArthur, who has introduced a bill on the issue in the Scottish Parliament.

He expects the legislation to be debated and possibly voted on at its first stage later this year, which could lead to Scotland becoming the first nation in the UK to permit assistance to those with terminal illnesses who wish to end their lives.

“Everyone is just one bad death away from supporting assisted dying,” McArthur told the FT, adding: “Among colleagues there is much openness towards finding reasons to support it, rather than excuses to oppose, as has previously been the case in the Scottish parliament.”

Under McArthur’s bill, patients must have an “advanced and progressive” terminal illness, while two doctors must judge that they are mentally fit to make the decision to end their own lives and rule out any concerns of coercion.

Because of the different rules in other parts of the UK, a patient would have to be resident of Scotland for at least a year to be eligible for assisted dying.

Campaigners in favour of changing the law in England believe a shift by the British Medical Association and the Royal College of Physicians to a neutral position on the issue after opposing assisted dying for decades could enable more MPs to back legislative change.

But despite the growing public support for a relaxation of the rules, there remains fierce opposition from some disability rights campaigners and medical figures.

Tanni Grey-Thompson, a former Paralympian who is a peer in the House of Lords, fears assisted dying would increase pressure on the old and disabled to stop “being a burden” on their families. The right to die would become a “duty to die”, she said.

Dr Gillian Wright, a former palliative care registrar and member of the Our Duty of Care, a campaign group opposed to what it refers to as assisted suicide, has argued that societies should be focused on “well-funded, accessible, high-quality palliative care for all”.

The “primary danger of assisted suicide is that individual lives are devalued by society because they are ill, disabled, confused, or that their contribution to society is perceived to be minimal”, she said.

But the experience of some families in countries that allow assisted dying challenges the warnings. Last summer Liz Reed travelled from England to Australia to be present at her brother’s assisted death in Queensland, Australia.

Robert Smyth had moved there from England with his Australian wife a few years earlier in search of a better quality of life. The couple never imagined they would soon be forced to confront his death.

Robert’s stage four lung cancer diagnosis came from “nowhere”, Reed said. “He was 39, young, very fit and healthy with a young family.”

She recounted the moments before a doctor administered a lethal injection, when the family sat in the sunshine in the garden of his hospice for their final moments together.

“Rob didn’t want his family to watch him fade away and disintegrate, which would have happened here in England,” Reed said. “He was at peace with his decision and we felt peace that he had been able to make it.”

[ad_2]

Also Read More: World News | Entertainment News | Celebrity News