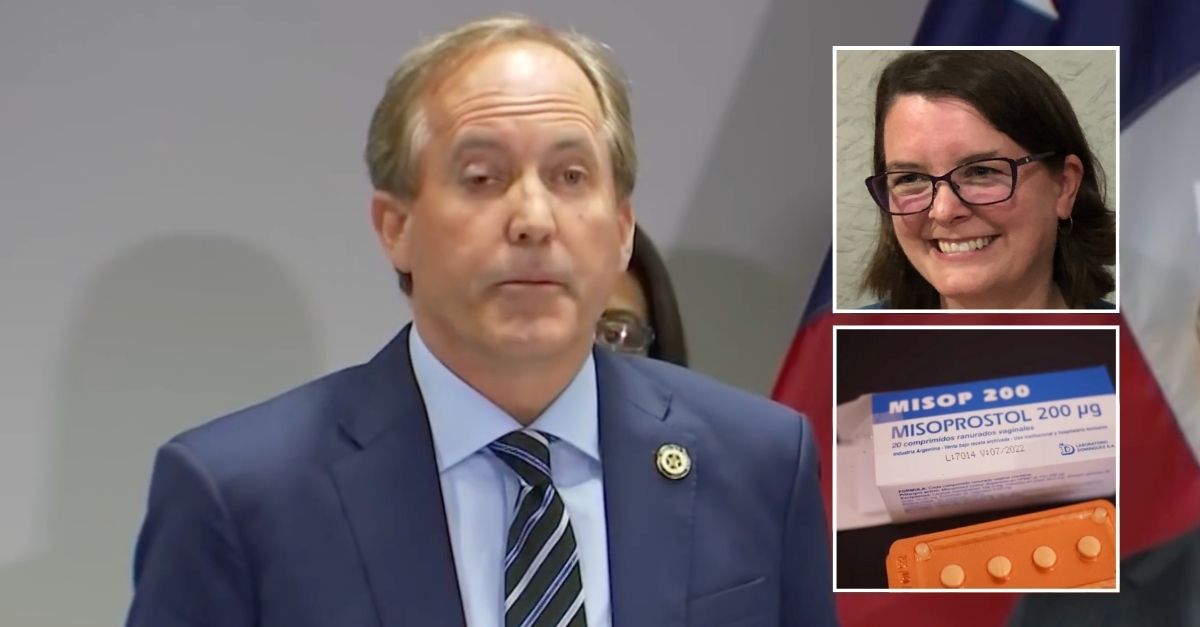

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has taken legal action against a doctor from New York accused of sending prescription pills through the mail to Texas. These pills are said to have caused complications for a young mother and resulted in the termination of her unborn child. This case is reportedly the first of its kind involving a cross-state legal battle relating to abortion.

Dr. Margaret Carpenter, the founder of the Abortion Coalition for Telemedicine, is at the center of the lawsuit. She allegedly mailed abortion-inducing drugs to a resident of Collin County in Texas between May and July. These drugs are not permitted in Texas but are legal in New York due to protective abortion laws.

The lawsuit filed by Paxton aims to explain the reasons behind the legal action and details the events that unfolded as a result of the alleged mailing of the abortion-inducing drugs.

“About mid-May 2024, a 20-year-old female resident of Collin County, Texas became pregnant,” Paxton’s complaint says. “The mother of the unborn child did not communicate her pregnancy to the biological father of the unborn child. The mother did not have any life threatening physical condition aggravated by, caused by, or arising from the pregnancy that placed her at risk of death or any serious risk of substantial impairment. The mother proceeded to utilize telemedicine or telehealth services and received, through Carpenter, two abortion-inducing drugs or prescriptions. The first was a box for the drug mifepristone, 200 mg, followed by the ‘#1’ and the directions to take 1 tablet by mouth and to ‘take this medication first.’ The second was a pill bottle of misoprostol 200 mcg with directions to take 4 tablets (i.e., 800 mcg.) after the mifepristone.”

On July 16, the complaint claims the mother asked the biological father if he’d take her to the hospital due to a “hemorrhage or severe bleeding.” Health professionals at a hospital in Collin County, Texas, told the father what was going on and noted that she “had been” nine weeks pregnant. The woman went on to allegedly lose the child.

“The biological father of the unborn child, upon learning this information, concluded that the biological mother of the unborn child had intentionally withheld information from him regarding her pregnancy, and he further suspected that the biological mother had in fact done something to contribute to the miscarriage or abortion of the unborn child,” the complaint says. “The biological father, upon returning to the residence in Collin County, discovered the two above-referenced medications from Carpenter.”

According to Paxton, Carpenter violated Texas law by providing “abortion-inducing drugs” to the pregnant Collin County woman, “which caused an adverse event or abortion complication and resulted in a medical abortion,” his complaint says.

“Carpenter’s conduct violates the Texas Health and Safety Code’s prohibition on prescribing abortion-inducing drugs via telemedicine,” the document notes. “Carpenter’s knowing and continuing violations of Texas law places women and unborn children in Texas at risk. Carpenter sees Texas patients via telehealth and prescribes them abortion inducing medication.”

So what happens when abortion laws and offenders in states like New York and Texas collide in court? Legal experts tell The Texas Tribune it’s complicated.

“Regardless of what the courts in Texas do, the real question is whether the courts in New York recognize it,” Greer Donley, University of Pittsburgh professor, told the newspaper.

“Slavery is probably the best historical parallel to what we’re seeing now,” said Kermit Roosevelt, a law professor at Penn Carey Law at the University of Pennsylvania, back in February as Paxton was going after abortion activists and demanding medical records from out-of-state clinics that provide gender-affirming care to minors.

“Obviously, that didn’t end well,” Roosevelt told the Tribune. “Well, it did, because we abolished slavery federally, but it was a tough road.”

Texas has been threatening to take legal action such as the Carpenter suit for quite some time, according to the Tribune, but the Paxton filing against Carpenter marks the first known instance of a lawsuit actually being file, the paper reports.

John Seago, the president of Texas Right to Life, told The New York Times in February that pro-lifers were waiting for the “right case” to strike.

“We can definitely promise that in a pro-life state like Texas with committed elected officials and an attorney general and district attorneys who want to uphold our prolife laws, this is not something that’s going to be ignored for long,” Seago said.

“Unless Carpenter is restrained by this Court, with relief that is enforceable by a contempt order, Carpenter will continue to defiantly violate Texas Law,” Paxton’s complaint says. “Carpenter’s continued violation of our Texas statutes as stated herein is probable and imminent. The State is not required to establish that it will prevail at trial to obtain a temporary injunction as it only needs to plead a cause of action and show a probable right to the relief sought.”

States like New York that have “shield laws” — there’s currently 22 of them — are supposed to protect healthcare workers from cross-state court challenges and investigations. They can do this in several different ways, one being through a denial of extradition.

“If Texas wants to arrest someone who’s in Washington State [shield law state], one of their residents, Washington doesn’t have to arrest that person and extradite them back to Texas,” Darryl Brown, a law professor at the University of Virginia School of Law, told the Tribune in February.

“Maybe a state like Wyoming prosecutes someone who bought marijuana in Colorado and came back to Wyoming, but it doesn’t set off a battle where Wyoming is trying to get someone back from Colorado or get evidence from Colorado,” Brown said. “States just haven’t disagreed with each other so sharply that they have come to loggerheads about this.”

In 1974, the Supreme Court ruled in Bigelow v. Virginia that a “state does not acquire power or supervision over the internal affairs of another State merely because the welfare and health of its own citizens may be affected when they travel to that State.” However, that ruling stemmed from the 1973 decision in Roe v. Wade, which is no longer in effect.

“The current U.S. Supreme Court, now that it has eviscerated Roe, could revisit Bigelow’s anti-extraterritoriality principle,” wrote legal scholars David Cohen, Greer Donley and Rachel Rebouché in a 2023 Columbia Law Review.

“Complicating this picture even further is how these rules apply to medication abortion,” the group said. “Abortion pills did not exist at the time of Bigelow and were not widely used at the time of Nixon. These medications can be legally obtained in one jurisdiction, one or both of the drugs can be taken elsewhere, and the pregnancy can end somewhere else entirely. In the immediate aftermath of Roe’s demise, abortion providers and lawyers reviewing medication abortion protocols are struggling to answer what had been a simple question with procedural abortion: Where does the abortion occur?”