Zeke Boyle’s love for old barns started when he was hired to dismantle one. An estate agent friend of his family was trying to sell a property in upstate New York; the mid 19th-century barn on the land was an eyesore, the seller complained, and best removed in order to snare the highest selling price.

Boyle picked up the gig to earn some pin money, but it changed his life. “I could not believe how difficult it was to get this building down, a large 1850s hand-hewn barn. Just trying to pull it apart was so difficult,” he recalls, five decades later. “I saw how intricate the joinery was, and I instantly acquired this admiration for the craftsmen.”

He promptly dropped out of engineering school to apprentice with an old carpenter and learn the skills he’d need to restore, rather than dismantle, those structures. And now, the 73-year-old is among the US’s foremost housewrights — more exactly, a barnwright — who helps others in his region to conserve and restore centuries-old wooden barns.

Boyle lives in New York’s Sullivan County, and New England as a whole is a hotbed of these structures — and interest in them has piqued in the aftermath of the pandemic. New residents have arrived — many of them from New York City — with the aesthetic instinct, and deep enough pockets, to undertake restorations that typically cost $200,000-$500,000. Most customers see these barns as bonus hobby areas, or high-end recreation rooms.

Those take many forms, whether a games room or woodworking room or a place to store antique car or tractor collections. Function tends to be secondary to their primary driver, which is to save and protect the historic structures.

These new locals are hiring Boyle and his peers with gusto, and have a particular penchant for barns that predate the civil war of 1861-65. “The older the better, as far as I am concerned,” Boyle says firmly.

Adam Carroll, a Hudson Valley-based estate agent with Compass, mostly works with high net worth buyers who are browsing in the area. “People love barns, and they’re much more interested in a barn on the property than, say, a pool,” he says. “It completes that fantasy of the upstate estate, and having that exterior building is important even if they don’t do anything with it, like making an art studio or a work space.

“And when you show someone a home with an old barn, they ask the same thing over and over — ‘Is it pre-civil war?’ That’s a dividing line for sure.” It’s not that newer barns are undesirable, Carroll adds, but rather that older designs will sell much faster and for much higher prices than even a design from the 1870s.

It’s no arbitrary marker, either, as there are several reasons why barns that predate Lincoln retain both cachet and value.

First, consider the wood. Many of the oldest barns were built from long-established trees that had grown slowly in New England’s dense, near-virgin forests, forcing them to compete for sunlight; the result was ramrod straight trunks with exceptionally resilient wood.

“They had the cream of the crop to work with,” says Boyle of the earlier builders, noting that one 1840s barn he restored had 55ft-long beams hewn from a single tree. “The timbers were so straight and square it’s unbelievable.” Pennsylvania-based fellow barnwright Douglass Reed agrees, noting that he’ll often encounter beams with 40 or more rings in every inch of wood while a typical plank at a hardware store today would have no more than four; it was the struggle to grow that created such density.

Put simply, the oldest barns are made from wood with unsurpassably durable qualities that delighted — and exhausted — their builders. Estate agent Carroll reaffirms his point: he’s just sold a property that had a giant dairy barn that the owners considered pulling down. A specialist wood recovery firm, which buys and resells old timber, offered $500,000 for the wood alone; had it been a couple of years older, and so predated the civil war, the company told Carroll it would have fetched $750,000.

There’s more to the allure of the oldest barns than their solid construction, though. The size of those beams conferred on the interiors an airy openness that remains compelling, with fewer internal struts and supports needed. Arron Sturgis is a Maine-based barnwright who directs an 18-strong team of restorers. “They’re built on the golden mean, so when you walk into a barn of that size, you feel the human geometry of it. I believe it’s very intentional,” he says, referring to the measure also known as the golden number or divine proportion.

The golden ratio between two numbers, or measurements, is 1.618, and has been deployed by architects, including Le Corbusier, for its purported harmonious properties. “You just feel good when you’re in them. That’s part of the allure.” Barns like these were also built first by settlers, who would live in them alongside their animals while they established a smallholding; since they were also intended for human habitation, they’re built to a higher standard than observers might assume.

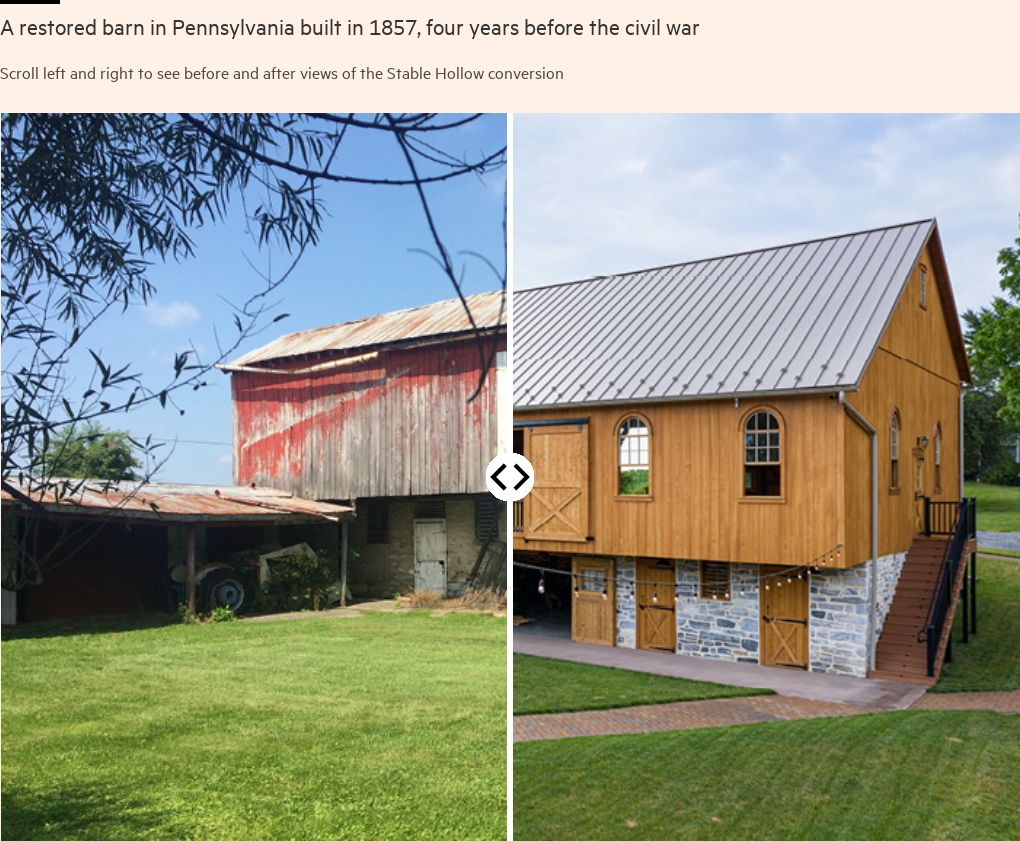

Two early settlers could clear, on average, around five acres of old-growth forest per year, so it could take about three years to establish enough land for a viable farm; in the interim, the felled logs could be used for this multipurpose structure. “These barns were often constructed before the houses or anything else,” says Diana Frazier of another Pennsylvania-based barn-restoring specialist, Stable Hollow. “It wasn’t just somewhere to store your animals, it was a meeting place. Fast forward 300 or 400 years, and there’s a natural appeal for these buildings to be a community centre again.”

Their hand-hewn nature is another aspect of their appeal. Think of hardware and nails smelted by the local blacksmith or the old-fashioned joinery systems such as tying joints, for instance, which Arron Sturgis calls “pervasive, long-lasting and very beautiful”. Moreover, the then-standard scribe rule, whereby joiners would leave their marriage marks visible on the frames, lends the woodworking equivalent of an artist’s signature to most barns of the era.

Sturgis says that it was economic changes rather than the political turmoil of the civil war that created the true dividing line in the 1860s between the now sought-after barns and their cheaper, more modern counterparts. Industrialisation brought circular saw mills across the country, replacing hand-hewn timbers with beams that were simultaneously both more exact and less soulful.

Farming methods shifted, too, as the booming country moved from a subsistence model to large-scale, mostly dairy operations, thanks to the emerging railroad network that allowed fresh produce such as milk to be delivered more quickly and farther afield. As farms grew, so did barns; an enlarged cowshed also used lighter-weight timbers.

“You don’t see heavy timber framing any time really after 1850,” says Sturgis. “That’s the real change, because farming changed. And the landscape changed dramatically, too — between 1800 and 1860, they cut everything down to make room for the large agricultural enterprises like this.” Those once-plentiful forests were comparatively threadbare by the end of that period, Sturgis claims. Remember there was also widespread sheep farming, mostly for wool — another crop that requires trees be felled in favour of open land.

Today, much of the onetime farmland of New England has been reclaimed as housing, the old farm cottages repurposed as homes, their empty barns standing nearby. Many of the incomers who hire barnwrights accept that the investment they’re making in a 200-year-old structure might not be fully recouped. But Sturgis says his clients are often conscious that there’s more than monetary value in these barns: “For us, working on barns is far deeper than putting sticks together, it’s living history.”

The different styles of European settlers — particularly, German, Dutch and English — are evident in the barn designs, which act as silent signposts to the past. “You can map their travel patterns in the buildings. The loss of these structures means you’re going to erase a whole cultural heritage.”

Find out about our latest stories first — follow @FTProperty on X or @ft_houseandhome on Instagram

Also Read More: World News | Entertainment News | Celebrity News