On a cold February night, the Special Air Service’s 12 men found themselves hiding behind a meager hedge on the outskirts of a chapel car park in the Northern Irish village of Clonoe for over three hours.

Their mission was based on intelligence indicating that the East Tyrone Brigade of the Irish Republican Army planned to gather their most powerful weapon at that location, ready to transport it on a truck.

The SAS members were prepared to swiftly intervene, capturing both the weapon and the terrorists before they could carry out their attack on the local police station.

For this was not just any old machine gun. Firing more than 600 armour-piercing 12.7mm rounds per minute, the Russian-made DshK (known as the ‘Dushka’) can stop a plane or armoured vehicle at a range of more than a mile.

Just one problem. At 10.40pm, the SAS realised that the intelligence they had received was not entirely accurate. Yes, the target was Coalisland police station. But as the distant sound of heavy gunfire made clear, the gun was already in full working order and battering the building (its occupants, forewarned, were down in the basement).

It seemed likely, therefore, that the chapel car park was now the place where the IRA would come to dismantle the ‘Dushka’ rather than put it together. The 12 soldiers steeled themselves for the arrival of this horrific killing machine.

A few minutes later, the soldiers could see headlights coming up the lane next to Clonoe chapel. A Vauxhall Cavalier was leading the lorry at great speed and both came careering into the car park – with three gunmen plus the Dushka clearly on the back of the lorry – followed by two more cars.

Suddenly, the Vauxhall’s headlights were illuminating the hedge.

Peter Clamcy One of four provisional IRA members shot dead in an SAS ambush at Clonoe, near Coalisland in County Tyrone in February 1992

Patrick Vincent was also gunned down

Also killed was Peter Clamcy

Sean O’Farrell was one of the four killed in February 1992

Had the SAS been spotted? If so, they were dead unless they reacted instantly. Jumping to their feet and opening fire, the soldiers ran forward and all hell broke loose.

Moments later, four terrorists lay dead, a wounded gang member was captured and another three escaped in the other vehicles, one of which was found abandoned and ablaze at a nearby sports ground.

The only SAS casualty was one walking wounded. A soldier had been shot in the face but the bullet had passed through his cheek and out again. The Dushka would never fire another shot in anger, with an untold number of lives saved as a result.

It was a major defeat for the East Tyrone Brigade but due process then kicked in.

The Royal Ulster Constabulary conducted an eight-month investigation into the deaths, and the Director of Public Prosecutions summoned the SAS commanding officer for interview.

After statements were taken from all the soldiers, the DPP issued a direction that there would be no prosecutions.

That was October 1992 and the matter was closed.

Or at least it was until 2024 when the soldiers were ordered to give evidence to a ‘legacy inquest’ into the four deaths. The SAS veterans exercised their right to silence, leaving the coroner with their signed statements from three decades earlier.

How the Daily Mail reported the Clonoe SAS operation that led to the deaths of four IRA members

Pictured: Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer speaks during a media conference at the end of the Nato Summit at the Hague

Pictured: A fireman searches through the wreckage of the Mulberry Bush pub underneath the Rotunda in Birmingham City Centre believed to have been caused by a bomb attributed to the IRA

The men then waited another year for the coroner, a senior Northern Irish judge called Sir Michael Humphreys, to produce his findings. He ruled that the shooting of the terrorists was ‘not justified’ thanks to Article 2 of the European Court of Human Rights whereby the state has ‘a positive duty to protect life’.

He ruled that ‘the soldiers did not have an honest belief that it was necessary in order to prevent loss of life’ and that the SAS’s use of lethal force was, therefore, ‘not reasonable’.

The soldiers, he declared, could have waited until the IRA had started dismantling the gun and then informed them that they were under arrest.

However, because they stood up and opened fire on the terrorists, he refused to believe that this was an arrest mission at all.

He made great play of the fact that, during the original investigation, the soldiers had referred to the operation as an ‘ambush’. Because they may, therefore, have committed a criminal offence – up to and including murder – Sir Michael was handing the case over to the DPP.

The 12 soldiers, now all veterans, some of them in their seventies, must wait to hear if they are to be arrested and charged.

‘It is, simply, beyond belief,’ says George Simm, Regimental Sergeant-Major of the SAS at the time of the operation. ‘There was no new evidence, none, And here we have a judge who presumes to know what to do in that split second when your men might be about to be killed.’

That is why Mr Simm (a holder of the Distinguished Conduct Medal, which sits just one rung below the Victora Cross) is talking to me over a cup of coffee in a London café. A year ago that would have been beyond belief, too. After 25 years in the SAS, he is marinaded in its codes of discretion and loyalty.

He was a rigorous enforcer of regimental codes, once expelling a retired general from a funeral wake at the SAS barracks in Hereford. Top brass he might have been, but the general had broken the code by including clandestine SAS operations in his memoirs.

Last year, however, the advent of the ‘legacy inquest’ prompted Mr Simm to put his name to a letter in the Times attacking the ‘incremental supremacy’ of the ECHR and the way in which successive governments have given Legal Aid to fund ‘vexatious compensation cases’ against British troops. Now, the naivety of the

Sir Keir Starmer talks to soldiers during a visit to the Netherlands marines training base during a NATO summit visit at the Hague

Pictured: The wreckage following an IRA car bomb attack outside the Parachute Brigade at Aldershot Garrison. Seven people were killed

Clonoe verdict has led Mr Simm – and others – to step out into the open on behalf of those comrades who face a potential prosecution.

‘The Government need to know that if this legal madness is allowed to continue unchecked, beyond the reach of Parliament, then this will defenestrate any security process in this country,’ he says. ‘Because human rights law, as it stands, now supercedes the rights of the security operator to do his job.’

Meanwhile, as Labour dismantles a law which was supposed to give veterans some sort of historic protection, more of these cases seem inevitable.

For many like Mr Simm, the Clonoe result is, therefore, a tipping point, a fork in the road, call it what you will. And not just for past and present members of the SAS. It threatens all those units involved in the very dangerous, thankless and yet vital covert operations combatting Northern Irish terrorism over three decades. It is why both the veterans and the Ministry of Defence are seeking a judicial review to overturn the Humphreys ruling.

It is why the Conservative MP and ex-SAS reservist Sir David Davis is now leading a parliamentary campaign to bring in new legal protections which stop old soldiers from being dragged out of their retirement to be investigated under laws which did not even exist at the time and which were not passed by the UK Parliament in the first place.

And it is why today the Daily Mail is proudly launching a new campaign with two overarching aims: protect the Special Forces veterans and stop rewriting history. For make no mistake. This is not just about compensation-chasing, publicly-funded lawyers running rings round a weak Northern Irish government, led, for the first time, by a Sinn Fein politician, and propped up by a seemingly bottomless Legal Aid budget.

According to its own data, handling ‘legacy’ issues has cost the police £126million over the last seven years while £18million has been handed to lawyers – versus just £7million to victims. The bill for the Clonoe hearing currently stands at £1.3million, according to the court, and that does not include the cost of police time.

Pictured: Children talk with British soldiers at a roadblock on a street in Belfast on September 21, 1969

This is also a case of hardline nationalists painting every IRA defeat and humiliation as a British crime. And that has dire implications for our future national security. ‘Clonoe was a great defeat for the IRA and Sinn Fein want to rewrite history and turn that defeat into a black operation,’ says Sir David Davis.

A senior Royal Ulster Constabulary veteran from the Clonoe era puts it to me: ‘The IRA can never look good. They shot people in their beds. But if they can make the SAS and the RUC look as bad as them, then they can justify their use of the bomb and the bullet.’ Having wearily dismissed television dramas like ‘SAS Rogue Heroes’, the veterans are now determined to correct the impression of fearless brigands tumbling out of the pub in search of a battle.

As all the Special Forces veterans I have spoken to in recent days point out, their activities were the most rigorously scrutinised in Northern Ireland, with every proposed operation pushed right up the chain of command and signed off at the highest level – even by the Secretary of State.

Recent allegations by the BBC’s Panorama about possible war crimes committed by British Special Forces in Afghanistan have only added to something of a siege mentality among SAS men past and present.

The SAS can cope with abuse, of course – and they are famously good at sieges. What is far more damaging is the corrosive effect on morale and reputation.

‘Right now, the chief topic of conversation in every mess in Hereford is: where does this go next?’ says Jamie Lowther-Pinkerton, a former SAS squadron commander at the time of Clonoe and former private secretary to Princes William and Harry. Like Mr Simm, he is another who is prepared to break cover and speak out for the good of the regiment.

‘Soldiers forfeit their rights to employment law, freedom of speech and all those other things we take for granted as long as they know that someone is watching their back. But who is watching it now?’

A silhouette of two special armed forces soldiers standing behind one another (file image)

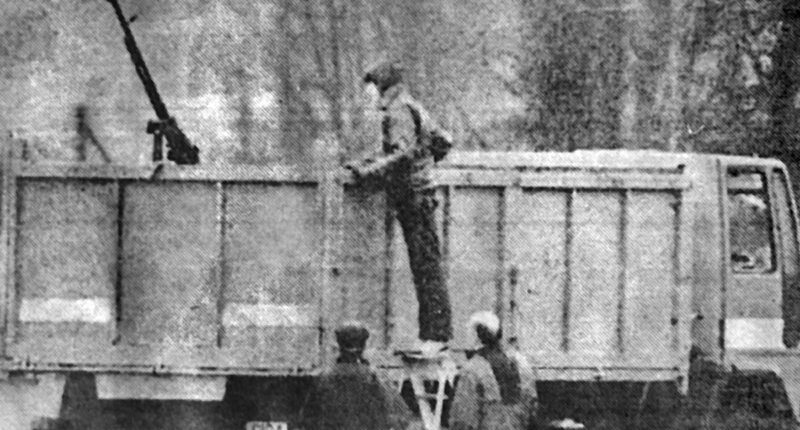

Pictured: The Russian made DHSK heavy machine-gun mounted on a lorry at Clonoe in 1992

Pictured: Masked members of the Irish Republican Army (IRA) escorting the coffin of Bobby Sands, who died on hunger strike at HMP Prison Maze in Northern Ireland

Mr Simm finds himself uttering words which he could never imagine saying before and which pain him greatly. When I ask him what a parent should tell a son (it remains an all-male unit) who might be thinking of joining the regiment, he grimaces. ‘I’d say to him: “Hell, no”.’ [His words are rather stronger than that]. Because it’s not the enemy you need to worry about now. It’s the lawyers.’

He points to the way that the last Tory government tried to halt the judicial over-reach of the lawyers and the ECHR with its Legacy Act to protect veterans. However, the courts have ruled that this Legacy Act is, guess what, in breach of the ECHR.

The Labour government agrees and so Sir Keir Starmer and his Northern Ireland Secretary, Hilary Benn, have pledged to repeal the Act. Meanwhile, the number of Troubles-related civil cases has shot up from 150 ten years ago to a current backlog of 1,100 – and rising.

It helps explain the phenomenal response to the recent petition on the parliamentary website under the heading ‘Protect Northern Ireland Veterans from Prosecutions’. Submitted in response to the Clonoe ruling, it demands ‘that the Government should not make any changes to legislation that would allow Northern Ireland Veterans to be prosecuted for doing their duty in combating terrorism as part of ‘Operation Banner’. (1969-2007)’.

If a petition receives 10,000 online signatures, the Government has to respond. After 100,000 it is supposed to be debated at Westminster. This petition sailed past both criteria in a week and a debate has been fixed for July 14.

The more people who click on the petition, however, the harder it will be for the Government to bat away so many awkward questions. In his current response to the petition, Mr Benn says meekly that the Legacy Act ‘has been found to be unlawful’ and ‘any Government would have to repeal unlawful legislation’.

‘Do they think we’re children?’ asks Mr Simm. ‘It’s only unlawful because a law passed by the UK Parliament has been declared unlawful by a law in Europe. I don’t want this to become a debate about leaving the ECHR but for God’s sake…’

A few days after my coffee with Mr Simm, I meet him again in London at what feels like a council of war. We are in a flat near Victoria Station where four very senior and experienced SAS veterans are discussing the best way to ensure the public understand the regiment’s case.

‘Any secret organisation has to have “omerta” or discretion,’ , says Lieutenant-Colonel Richard Williams, a Military Cross-holder who commanded the regiment in Iraq. ‘You have to have discretion.

The ethos in the regiment has always been humility and humour. It’s quite an awkward thing if you’ve been in special forces being asked to talk about everything you’ve done. It’s not good for teamwork.

But if there isn’t any presentation of our point of view in the public domain, those who have got the critical view of us will be the only one that fills the space. And that’s very, very dangerous.’

So the old soldiers who are now speaking out under the banner of ‘justiceforveterans.uk’ are also taking great care to liaise with the regimental association, which represents all SAS veterans.

For many, one of the most irksome elements of inquests like Clonoe is the way in which so many regimental secrets have been dragged into the public domain through compulsory legal disclosure. There is nothing questionable about their tactics but it pains them greatly to have to place closely-guarded details about operational procedures into the public domain – and thus available to future foes.

‘An inquest is supposed to establish who has died and ask when, where and how,’ says Aldwin Wight, former SAS commanding officer (who won the Military Cross in the Falklands). ‘But now under Article 2 it has widened out massively into “who planned it”, “what was their state of mind” and so on and you’ve got judges being tactical commanders.’

n the foreground is a Russian DHSK 12.7mm heavy machine gun that was one of two supplied by Colonel Gaddafi in arms shipments to the IRA

I hear the same despair among RUC veterans who worked right alongside the SAS. Visiting Northern Ireland last week, I heard time and again how blundering officials and politicians have risked lives with careless talk.

One former senior RUC officer still winces at the memory of former Northern Ireland Secretary Mo Mowlam telling a very senior IRA godfather: ‘You need to be careful what you’re saying in that house!’ Whereupon the IRA’s counter-espionage unit tore apart the house in question and duly found two, tiny (and legally-sanctioned) listening devices. British undercover soldiers and police had risked their lives to install those. Yet Ms Mowlam had blown up a vital intelligence source with one glib remark.

It all feeds into a legitimate frustration that this entire ‘truth and reconciliation’ process is entirely one-way and asymmetrical.

The SAS believe they are fair game because they kept records and the ECHR imposes the highest standards on ‘state actors’. The IRA, however, are not compelled to produce any records and no longer have to answer for unsolved murders since receiving ‘comfort’ letters from the Blair government in 2006.

While they and their apologists still deploy military language and talk of heroes on ‘active service’ when it suits them, they swiftly fall back on the ‘innocent civilian’ excuse when it does not.

‘When Blair let the terrorists go free, the first Republican terrorist out was Henry Louis McNally,’ says Mr Simm, recalling the IRA’s 1988 attempt to plant a bomb in a culvert next to the road leading to and from a housing estate for Army families.

‘So we had to eat that.’ Bob Parr, trawlerman-turned-Royal Marine-turned-SAS surveillance officer in Northern Ireland, says that the politicians are pursuing a process of what is often called ‘transitional justice’, as in post-apartheid South Africa, except that this one, he says, is subject to ‘distributive inequality’.

‘Here you have a process that is fundamentally skewed. We now see paramilitaries being legally privileged over actors of the Crown which includes the SAS.’

George Simm says he tears up the various letters he receives asking him to take part in ‘reconciliation’. He says: ‘Those who set out to murder and plant bombs made choices.

I will go to my Maker with my head held high for trying to stop them.’ The Clonoe verdict has serious flaws, as we will see in the weeks to come. However, these veterans believe it may ultimately serve a purpose.

‘We have beaten most foes, since our origins. We’ve lost a few things, but we’ve tried to prevail,’ says Mr Simm.

‘What we can’t beat is our own side – and that’s the main threat to us right now. At least Clonoe has brought things to a head. And this is just the start.’

Indeed it is. Now the onus is on those of us who will never have to stare a Dushka in the face to do our bit, too.

Sign the Parliament website petition calling for protection from prosecution for Northern Ireland veterans: