Just the other day, a local technical college near Stuttgart, Germany, rang Kai Höss with alarming news. Someone had been etching swastikas on the doors of the loos.

This followed a number of student protests against Israeli operations in Gaza. Might Kai give a talk to the students?

He did not hesitate. Days later he was addressing a packed assembly, reading a first-hand account of scenes from the death camp at Auschwitz.

Of two small boys, newly arrived off a cattle truck and so engrossed in a game of tag that they failed to heed the command to follow the rest into the gas chamber until the commandant ordered two guards to pick them up and throw them inside.

Of a frantic mother trying to wedge the doors open and force her children out, screaming: ‘Why don’t you at least let my precious children live?’

‘People were in tears – including me,’ Kai tells me. ‘And so they should be. If this stuff doesn’t get you from here to here [he points from his head to his heart], then it hasn’t sunk in. It’s just another history lesson.’

The college has asked him to come back and give the same talk to those who could not be accommodated last time.

He is happy to oblige. Germany never takes the appearance of swastikas lightly, of course. But Kai speaks with a unique authority. The author of those accounts was not some terrified witness. He was Kai’s grandfather Rudolf Höss, commandant of Auschwitz and one of the most brutal criminals of the Second World War.

The gaunt faces of children behind the wire at Auschwitz as it is liberated by the Russians on January 27, 1945

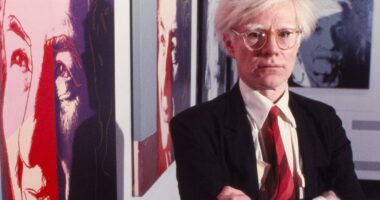

Rudolf Höss with aides at Auschwitz. He was the commandant of Auschwitz and one of the most brutal criminals of the Second World War

Tracked down by the British after the conflict, he laid it all out in the chillingly clinical memoir he wrote as he awaited his date with the gallows in April 1947.

‘No one wants to be Rudolf Höss’s grandson,’ Kai, 62, tells me over a cup of tea at his home near Stuttgart. ‘Every day I must face the fact that I am descended from the worst mass-murderer in history.’

While some might want to put as much distance as possible between themselves and such a dark family past, Kai takes the opposite view.

A hotel manager turned evang-elical pastor, this father-of-four wants to ensure future generations never forget the horrors committed by his grandfather’s generation. In particular he wants to do what he can to stem the Gaza-fuelled rising tide of anti-Semitism in Western democracies.

He is determined to debunk any attempts to use moral relativism to compare Israel to the Nazis, let alone accuse the Jewish state of ‘genocide’ and thereby demand the dismantling of Israel.

‘You hear those demonstrators shouting ‘from the river to the sea’, but they don’t even know which river – or which sea,’ he says, shaking his head.

‘There’s all this emotional energy but they don’t understand what it’s really about. Hamas’s strategy was to bring Israel to the point where they get mad and hit hard so the world rises against Israel.

‘So Hamas had to do something really bad [on October 7, 2023] and Israel retaliated. Wouldn’t you, if 1,200 people had just been murdered in their beds?

‘If I was Israel, I’d go after Hamas too and complete the job. But I would also love those Palestinians at the same time.’

Kai Höss, 62, right, talking to Robert Hardman. Rudolf Hoss was Kai’s grandfather

As an assiduous student of the Bible, he rattles off all those sections that talk about anti-Semitism through history. ‘God chose the Jews to be the showcase nation and others have been attacking them ever since. So we have to protect them, to pray for them – because people are all capable of doing crazy stuff.’

Tomorrow, the eyes of the world will fall on Auschwitz, an hour’s drive from Krakow in Poland. World leaders, including the King, will congregate there for Holocaust Memorial Day.

It was on January 27, 1945 that the camp (really a network of camps) was liberated by Soviet forces who found a handful of starving survivors staring in disbelief from behind barbed wire.

In 2005 the international community decided that this day should be formally recognised as Holocaust Memorial Day. But no single date can possibly do justice to the horrors of an industrial genocide lasting years and spread across a continental network of death camps which have become bywords for cruelty – Dachau, Buchenwald, Treblinka, Bergen-Belsen…

Since Auschwitz was the most extensive and hellish of them all, a killing zone for a million Jews, plus other minorities, it serves as the focal point for remembering the greatest atrocity in modern history.

And its pre-eminence was largely down to one man, its long-serving commandant, Rudolf Höss. After winning an Iron Cross as a teenager in the First World War, he abandoned plans for the Catholic priesthood. Instead, he joined a Right-wing paramilitary militia and was eventually jailed for murdering a suspected communist.

Once the Nazis came to power, Höss was released and given a job running a new prison camp for enemies of Hitler at Dachau, near Munich. Höss’s capacity for brutality and hard work singled him out for promotion through the ranks of the dreaded SS.

While serving at another camp, Sachsenhausen, near Berlin, he was even ordered to execute a fellow SS officer who had been arresting a political subversive and had allowed the man a few moments to say goodbye to his family. The prisoner had then escaped. The SS rule for such a ‘duty violation’ was death.

Rudolf Hoss’s five young children, including Kai’s father Hans-Jürgen Höss. The Höss family enjoyed riding, fishing and even had a swimming pool

An image of a woman’s barrack in the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp

‘The condemned man was a decent person in his middle thirties, married with three children, who had been conscientious and loyal in his duties prior to this incident. Now he had to pay the penalty for his good-heartedness,’ wrote Höss, adding, with a morsel of remorse, that he had been very ‘upset’ as he administered the coup de grace into the back of his comrade’s head.

Promoted to Auschwitz in 1940, he progressed from incarcerating subversives to implementing Hitler’s ‘Final Solution’ directive to exterminate Europe’s Jewish population on an industrial scale.

A vast new sub-camp was constructed at nearby Birkenau, with rail platforms leading straight to those gas chambers and crematoria that have entered the history books.

The death toll under Höss would exceed a million, making his operation the most ruthless and efficient in the Third Reich. He lived alongside the main camp in a spacious house with his wife Hedwig and their five young children, including Kai’s father Hans-Jürgen Höss.

While unspeakable crimes were being perpetrated over the garden wall, the Höss family enjoyed riding, fishing and even a swimming pool. This grotesque parallel world of domestic happiness alongside carnage was the subject of last year’s Oscar-winning film The Zone Of Interest, based on a novel by the late Sir Martin Amis.

More powerful still is the recent documentary film The Commandant’s Shadow, Daniela Völker’s haunting but uplifting masterpiece (now on Sky, Amazon, Apple TV et al). It follows two families coming to terms with what happened here and builds to an astonishing

conclusion. There is the indefatigable Anita Lasker-Wallfisch, who survived because she was picked to play the cello in the camp’s women’s orchestra and later built a new life in Britain. Her daughter Maya, born long after the war, says that she still suffers the inherited trauma that has blighted her own life.

What still confounds Kai is why his grandfather went down the path he did. ‘I believe he was an easy picking for the Devil,’ he says

We also see Hans-Jürgen coming to terms with his family’s past as he finally forces himself to read his father’s memoir and then makes a remorseful return to Auschwitz, along with both Kai and Maya (Anita refuses to go).

They tour the Höss family home and garden where Hans-Jürgen would play as a boy. They spend days on the other side of the wall, wandering tearfully through the abandoned gas chambers, crematoria and barracks.

Finally, the commandant’s son and grandson travel to Britain to meet Anita, an encounter that might have been unbearably awkward but which she describes as ‘beautiful’.

The film was released not long before Hans-Jürgen’s death last month. ‘He didn’t want a funeral or any sort of ceremony, just his ashes scattered on the Baltic,’ says Kai, who accepts he is now the surviving link to a man who came to embody man’s inhumanity to man.

Hence his determination to make best use of that role in two ways. As a pastor, he wants to champion the healing powers of the Bible. Equally important, however, is his quest to combat anti-Semitism through a new Christian-Jewish faith group called Bridges of Grace.

It is why he will spend Holocaust Memorial Day as a guest at a synagogue in Germany. A few weeks later, he will return to Auschwitz with a contingent from the US military, some of whom are members of his congregation.

‘I was asked to give a talk at this base for US special forces and, at the end, this huge man marches up to the stage. He’s built like a house and I’m wondering if he’s going to hit me.

‘Then he throws his arms around me and whispers in my ear, ‘Brother, I just want to let you know my whole family was murdered at Auschwitz – all gone – and I love you brother and I forgive you.’ I never forget that voice now.’

In his final letter to his wife and children before being hanged, Rudolf Höss urged his wife Hedwig to change the family name, writing: ‘You, my poor ones, have suffered unnecessary problems time and again because of my name.’

They did not drop Höss, though the past was seldom discussed at home. However, Hans-Jürgen would later recall the family receiving the odd mysterious aid parcel ‘from South America’.

Kai only learned about his family after the subject came up at school. He remembers Hedwig, who died in 1989, as ‘very prim and proper’ but she never once mentioned her husband.

She had stayed loyal to Höss after the war when he fled westwards, assumed a fake identity and was working on a farm near the Danish border.

Hedwig and the children were not far away, living in a sugar factory and always insisting their father was dead whenever British Army investigators turned up.

Finally, when the British warned her that they were about to hand over her eldest son to the Russians for imminent deport-ation to Siberia, she cracked and revealed Höss’s whereabouts. That same night, British troops surrounded the farm and knocked on the door. Recollections vary over what happened next.

In his acclaimed book Hanns And Rudolf, author Thomas Harding quotes his great-uncle Captain Hanns Alexander, saying that he thrust a revolver into Höss’s mouth and threatened to cut off his finger till he surrendered his wedding ring (inscribed with his name) while the soldiers set about him with pickaxe handles.

A previously unpublished testimony from Werner Haas of 92 Field Security Section, which made the arrest, paints a slightly different picture.

‘One of the team and the doctor knocked on the door. Höss opened it and was immediately knocked unconscious,’ recalled Mr Haas, a German child refugee who went on to join the British Army and lived in Westbury-sub-Mendip, Somerset, until his death last year.

He continued: ‘The doctor then examined him thoroughly for any capsules of poison but did not find any. He was then taken into a small room where he was asked just one question, and one question only, over and over again, ‘What is your name?’

‘Each time he answered ‘Franz Lang’ he was punched until the doctor told the chaps to go easy. After about seven or eight minutes he realised the game was up and gave his real name.’

What still confounds Kai is why his grandfather went down the path he did. ‘I believe he was an easy picking for the Devil.

Hitler was demonic and he swallowed all that,’ he reflects.

For Höss’s grandson, the most troubling part of visiting Auschwitz has been the railway platforms. ‘As a father, I was visualising these trains rolling in from all over,’ he says.

‘Some had already died on the journey and these poor people were just hauled off the train – and sent left or right – with the pregnant women and little children and the aged sent left… and it was my grandfather who devised the scheme. How could his conscience not get the better of him?’

The final judgment, then, from the commandant’s grandson? ‘I can’t judge him,’ he replies. ‘Only God can do that.’