In the past, one of the most impressive and influential individuals was Clive Of India, who lived 260 years ago. He was an English governor of Bengal, known for his audacious actions and insatiable desire for wealth.

Following a victorious battle, Clive was granted access to the palace treasury by a thankful Indian ruler. Inside, he was surrounded by piles of gold and silver objects, jewels, and other valuable items, encouraging him to take whatever he pleased.

He walked off with the modern day equivalent of about £400 million – and later said he was astonished by his own moderation.

This anecdote draws a troubling parallel to the present day, where the British Government is considering a proposal that could result in relinquishing a vast portion of our national riches to the contemporary counterparts of Clive – the billionaire tech moguls from California.

Advocates of the digital revolution love to claim that humankind is on the brink of something unprecedented with the development of Artificial Intelligence (AI).

There is, in fact, nothing unprecedented about the ever more greedy and ambitious rise of Big Tech.

We’ve seen this phenomenon before, though we might not immediately recognise it in its earlier form – the empire building of Clive’s East India Company (EIC). This trading behemoth, at its zenith, was the largest corporation in the world, based in the City of London.

In the 18th century, the rising political power of The Company was driven through the booming trade with Asia.

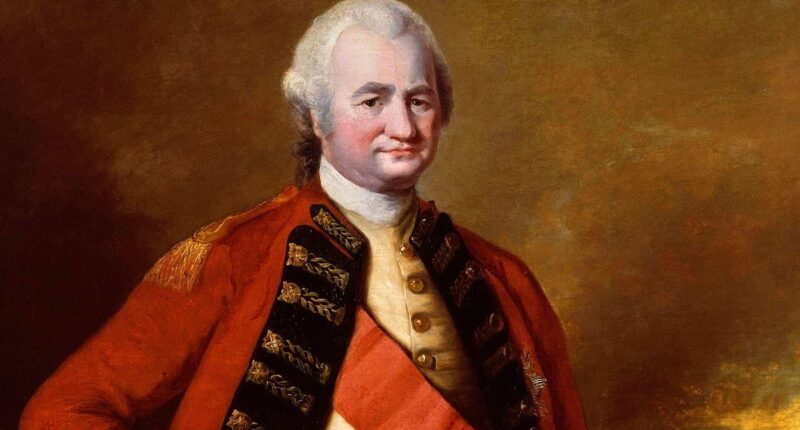

Portrait of the 1st Baron Clive, commonly referred to as Clive of India

Mark Zuckerberg talks about the Orion AR glasses during the Meta Connect conference on Sept. 25, 2024, in Menlo Park

SpaceX and Tesla founder Elon Musk speaks during an America PAC town hall on October 26, 2024 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania

Now it is the giants of Silicon Valley who aim to rule the world through the internet.

Software created by Microsoft, Google and Meta is evolving at extraordinary speed and already able to emulate human speech and syntax.

Mega-rich innovators such as Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg envisage an imminent era when their ‘large language models’ are able to reason as reliably as we do – or even more so – and achieve feats of imagination impossible in the human brain.

They might even – though this is further off – become fully sentient and self-aware, able to think for themselves.

But, as the Mail in conjunction with the entirety of Fleet Street has been warning recently, AI is being fuelled by wholesale theft.

The software is trained with screeds of novels and textbooks, newspaper journalism and magazine articles, trillions of words that are shovelled into its processors with appalling disregard for the international laws of copyright.

Whatever good comes from this will clearly not belong to its true creators, the writers who painstakingly produced those original texts. These include a stockpile of 190,000 books known in the tech industry as The Pile, among them international bestsellers.

It seems astonishing that super-successful novelists, even those with a thorough understanding of the law such as Americans Scott Turow and John Grisham, can be fleeced of their life’s work by a computer program. But that’s how empires are built. The invaders start by taking whatever they want.

Robert Clive and Mir Jafar after the Battle of Plassey, 1757. Francis Hayman, 1760

Aerial view of San Carlos in Silicon Valley

When they are challenged, they offer to make a deal. But the deal is never fair, because one side is expected to give up everything without understanding why the other side needs it.

Big Tech is doing exactly that, by trying to bounce the British Government into an agreement that makes no economic or moral sense. Our creative industries, which contribute £126 billion to the UK’s annual Gross Domestic Product, are being placed at the full disposal of AI developers, for almost no recompense.

To understand how this can be possible, we need to look back into history. The East India Company was the forerunner of Silicon Valley, not just because it possessed wealth beyond imagination but because that wealth generated vast power for a few unaccountable men.

To read the gripping story of the EIC, even in brief, is to notice uncanny parallels with the rapacious behaviour of Big Tech today. Though it morphed over time into a military and political arm of the state, The Company began in 1600 as a ‘passion project’, triggered by the excitement of global exploration.

The Spanish, a century earlier, had discovered the Americas by accident. Christopher Columbus, on a mission for Queen Isabella of Spain and her husband Ferdinand, was searching for a westward passage to China but stumbled on the Caribbean islands. Future expeditions found the American continents.

Gold brought back by the shipload financed the Spanish empire, as well as keeping English privateers busy. After Sir Walter Raleigh claimed Virginia for the throne (it was named after our Virgin Queen), Elizabeth I granted a royal charter to the East India Company in 1600.

During the next two centuries, the EIC came to dominate world trade in tea, cotton and spices, and generated vast profits for its backers. Londoners with money to invest in The Company could expect yearly returns of up to 30 per cent.

At its peak, the EIC was larger than several nations – but that dominance did not come without a fight. During the mid-1700s, France, Holland and Denmark joined forces with local potentates in an effort to wrest trade from Britain. The turning point came in 1756, when 123 British and allied Indian prisoners of war were massacred in the notorious Black Hole of Calcutta.

From then on, the East India Company used increasingly aggressive tactics. Robert Clive – a clerk who had risen to command The Company’s army – joined in the local political game, playing one ambitious ruler against another.

Christopher Columbus by Sebastiano del Piombo

By 1765, at the age of 35, Clive’s personal fortune was estimated at around £800 million in today’s money. Though he was regarded as a national hero, many MPs felt the EIC wielded too much power: writer Samuel Johnson, theologian John Wesley and philosopher Edmund Burke were among its vocal critics.

Instead of retreating, The Company offered a blatant bribe to the UK government: £400,000 (perhaps £1 billion today) in exchange for the freedom to expand its operations in India. Permission was granted, its share price soared and the EIC became a quasi-state.

The direct parallel with Big Tech bosses today is inescapable. Facebook and

TikTok can exert a grossly undemocratic influence on elections, while X owner Elon Musk is the unelected official in charge of cutting America’s federal budget.

Just as the East India Company pitted local rulers against one another – ‘divide and conquer’ is a favourite tactic of the tech companies today, playing on lack of co-operation between nations.

India’s largely agrarian kingdoms were dazzled by the promise of Britain’s industrial technology. But it was tech they didn’t understand, just as the true intricacies, potential and pitfalls of AI are only known to a few today.

Under Clive, the East India Company built up its private army to 260,000 soldiers, double the size of the British Army, and became ‘too big to fail’.

Again, the modern parallels are ominous. If our Government becomes completely reliant on US tech firms, the entire country can be held to ransom.

Yet the EIC brought many benefits. The building of India’s railways began under its administration, as did major cultural, educational and infrastructure projects, including the first ever museum in India, the country’s first engineering college, the first medical college teaching Western medicine outside Europe, law courts, banking, postal services and much more.

Similarly, Big Tech has revolutionised the way we communicate, putting super-computers in our pockets and giving even the poorest parts of the world access to education. AI could yet improve our lives in myriad ways, not least by diagnosing medical conditions with greater speed and accuracy.

Like the EIC before it, Silicon Valley has made more money and obtained more power than anyone could have imagined possible at the beginning of this century.

And just as the lives of millions of Indians were once determined in offices in London, so now we live our lives today in the hands of California’s tech gurus.

Whether they will control our future, too, is up to us.

– Professor Robert Tombs is the author of The English And Their History, published by Penguin.