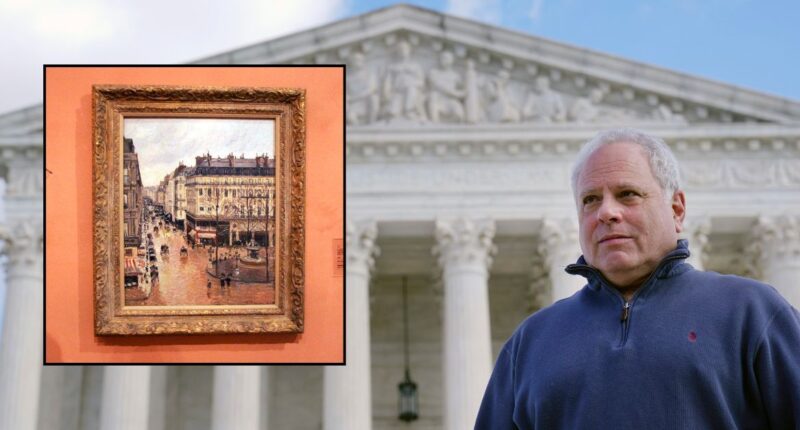

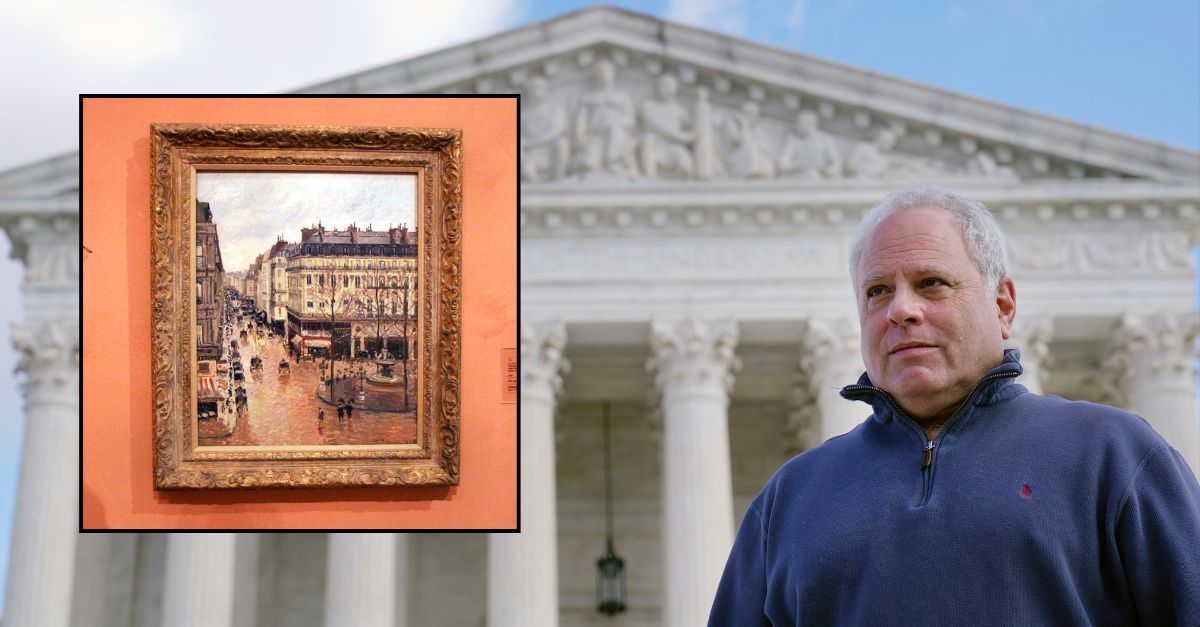

Main: FILE – David Cassirer, the great-grandson of Lilly Cassirer, poses for a photo outside the Supreme Court in Washington, Jan. 18, 2022 (AP Photo/Susan Walsh, File); Inset: FILE – This May 12, 2005 file photo shows the Impressionist painting called “Rue St.-Honore, Apres-Midi, Effet de Pluie” painted in 1897 by Camille Pissarro, on display in the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid (AP Photo/Mariana Eliano, File)

Despite federal courts having repeatedly ruled that a Spanish museum lawfully obtained an impressionist painting stolen by Nazis in 1939, the Supreme Court handed the descendants of the original owners a huge win Monday, which may well mean that they will be able to recover the artwork that once hung in their family’s Berlin apartment.

A painting’s journey through Paris, Berlin, California, and Madrid

The painting, “Rue Saint-Honoré in the Afternoon. Effect of Rain,” is a Paris streetscape by impressionist master Camille Pissarro valued at approximately $40 million. Pissarro was an early Danish-French impressionist painter who has been credited by some as launching the art movement that would come to include Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Paul Cézanne, and many others. Pissarro painted Rue Saint-Honoré during the winter of 1897-98 in Paris from the window of his hotel in the place du Théâtre Français.

In 1900, art agent Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel sold the painting to Paul Cassirer, a prominent German-Jewish art dealer who was a key promoter of the works of Vincent van Gogh.

26 years later, Cassirer died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound. Upon his death, his sole living relative, Lilly Cassirer, inherited the Pissaro and displayed it in her home in Berlin. In 1939, Lilly was forced by the Nazis to “sell” the painting for 900 reichsmarks — approximately $360 — in exchange for an exit visa to England. Lilly emigrated to the U.S., believing the painting was lost forever. In 1954, the U.S. Court of Restitution awarded Lilly $13,000 in restitution from the German Federal Republic.

Unbeknownst to the Cassirers, Pissarro’s masterpiece had also traveled to the U.S. and was acquired by a California gallery owner in 1951. Between 1951 and 1976, the painting changed hands multiple times until German steel scion Baron Hans Heinrich von Thyssen-Bornemisza bought it on consignment. Much later, in 1993, the baron created a foundation and began the Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum in Madrid, to which he sold the Pissarro.

Claude Cassirer — Lilly’s grandson — saw the painting in the Madrid museum and recognized it as something that had hung on the parlor wall in his grandmother’s home where he played as a child. In 2005, the Cassirer family began legal action to recover the artwork. Lilly died in 2010, and Claude’s grandson, David Cassirer, has continued the legal battle against the museum to recover the Pissarro.

The museum does not dispute that the Cassirer family was forced to turn the painting over to the Nazis, but maintains that Spanish law supports its rightful ownership of the work.

“A green light to looters”

A central legal question in the dispute between the museum — which maintains rightful ownership of the painting — and the Cassirer family is what law applies to the case. Given that the locus of the dispute is unclear, the applicable law is a rather complex legal issue.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled unanimously in April 2022 that California choice of law rules apply to the Cassirers’ restitution claims. This then raised a secondary legal issue as to what substantive law should be applied per California’s procedural rules.

California property law does not allow a possessor of stolen property to ever acquire rights superior to those of the true owner until the statute of limitations expires. By contrast, Spanish property law permits a person who acquired stolen property to obtain some rights in that property in some circumstances. The Cassirers maintain that Spain’s law should be ignored, because it is both archaic and out of step with international norms regarding Nazi-looted art. The Biden administration supported the Cassirers’ argument in the case.

In January 2024, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit ruled that California procedural law dictates the application of Spanish property law in the case — a devastating loss for the Cassirers. The appeals court based its ruling not on the underlying fairness of the outcome, but on the case’s strong connection to Spain as compared with its rather weak connection to California.

At the time, the Cassirers’ legal team slammed the Ninth Circuit’s ruling as “a green light to looters around the world,” and said their clients are especially motivated to continue challenging Nazi-looted art in light of the “explosion of antisemitism in this country and around the world today.”

A new California law, Assembly Bill 2867, was enacted in September 2024, which requires courts to use California law when hearing cases filed by California residents or their families to recover stolen art or other significant artifacts held by museums.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom, a Democrat, acknowledged at the time that the law was specifically meant to take aim at the Cassirer case and others like it. He said in a statement:

For survivors of the Holocaust and their families, the fight to take back ownership of art and other personal items stolen by the Nazis continues to traumatize those who have already gone through the unimaginable. It is both a moral and legal imperative that these valuable and sentimental pieces be returned to their rightful owners, and I am proud to strengthen California’s laws to help secure justice for families.

Once the new law was in place, David Cassirer appealed to the Supreme Court and urged the justices to reconsider the case. The justices agreed and on Monday, issued an unsigned four-line order granting Cassirer’s petition for certiorari, vacating the Ninth Circuit’s decision, and remanding the case with instructions to consider the dispute in light of California’s new law.

“I am very grateful to the Supreme Court and the state of California for insisting on applying principles of right and wrong,” David Cassirer said in a statement Monday. “As a Holocaust survivor, my late father, Claude Cassirer, was very proud to become an American citizen in 1947, and he cherished the values of this country.”

“He was very disappointed that Spain refused to honor its international obligations to return the Pissarro masterpiece that the Nazis looted from his grandmother,” Cassirer continued. “Although he passed away during this long battle, he would be very relieved that our democratic institutions are demanding that the history of the Holocaust not be forgotten.”

Likewise, Cassirer attorneys David Boies, David Barrett, and Steve Zack said:

We are grateful the Supreme Court has vacated the Ninth Circuit decision and remanded the Cassirers’ case for application of California law requiring the return of looted artworks to their rightful owners. There has never been a dispute that the Cassirer family was the rightful owner. With the applicable law now clearly established, we look forward to finally obtaining justice for the Cassirer family after twenty years of litigation. We hope Spain and its museum will now do the right thing and return the Nazi looted art they are holding without further delay.

Thaddeus J. Stauber, a Los Angeles lawyer who represents the Spanish museum, told the L.A. Times that the legal dispute is not yet concluded.

“Today’s brief order gives the 9th Circuit the first opportunity to examine if the new California Assembly Bill is valid and what, if any, impact it may have on the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection Foundation’s repeatedly affirmed rightful ownership,” Stauber said Monday. “The foundation, as it has for the past 20 years, looks forward to working with all concerned to once again ensure that its ownership is confirmed with the painting remaining on public display in Madrid.”

Love true crime? Sign up for our newsletter, The Law&Crime Docket, to get the latest real-life crime stories delivered right to your inbox.