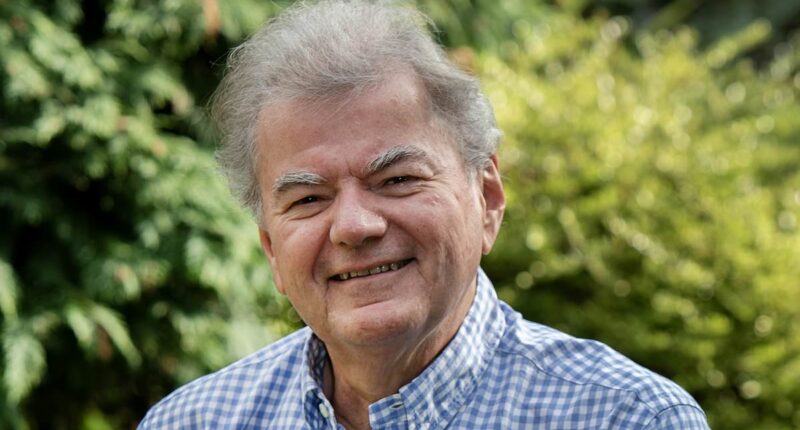

A new type of implant, resembling a wafer, has been developed to alleviate pain and dissolve in the body, potentially aiding in the recovery process following knee replacement surgery. Markus Rasche, a 64-year-old retired software company executive and father residing in Monk Fryston, North Yorkshire, was among the initial recipients of this innovative implant. He shares his experience with PAT HAGAN.

THE PATIENT

During my late 40s, I started noticing occasional stiffness and discomfort in my right knee. Being an avid handball player for years, I initially attributed it to overexertion from the sport.

To manage the discomfort, I would sporadically take pain relief medication such as paracetamol or ibuprofen. I simply tolerated the pain until a pivotal moment during a business trip to Frankfurt in my mid-50s when my knee gave out while I was boarding a train.

I fell between the train and the platform but thankfully I wasn’t seriously injured.

While in Germany I saw an orthopaedic expert who took X-rays and said I had severe osteoarthritis in my right knee.

He said there was very little cushioning cartilage left, and it wasn’t a question of if I’d need knee replacement surgery, but when.

By my early 60s, however, the pain was so bad that walking around the supermarket was impossible.

My GP referred me to hospital to explore my options.

Retired software company boss Markus Rasche (pictured), 64, a father-of-one from Monk Fryston, in North Yorkshire, was one of the first to benefit from a new pain medication for those undergoing knee replacement surgery

I met Professor Hemant Pandit, who explained that I’d need a total knee replacement but that it was a major operation which could result in considerable pain afterwards and I might take up to a year to make a full recovery.

But then he mentioned that the hospital was involved in an international study trialling a new, wafer-like dissolvable implant. It’s packed with a local anaesthetic drug called bupivacaine and is placed inside the new knee at the end of the operation.

I agreed to take part, even though I knew there was no guarantee I’d be given the wafer and might be in the control group getting standard pain relief.

Post-operation in May 2023, I took just one dose of morphine at 2am, when I couldn’t sleep from the pain, but that’s it.

Despite a 10cm wound down the front of my knee, I could bend it almost immediately.

Given how little morphine I needed, it seemed likely that I had been given the dissolving implant – this was confirmed months down the line when the study ended.

Within a few days I was back home and just four weeks after surgery I was well enough to go on holiday to Tenerife.

Eight months later, in January 2024, I had my left knee done with the standard technique and this time no dissolving implant.

Mr Rasche had knee replacement surgery on one of his knees using the new wafer-like implant that soothes pain before dissolving. Post-operation, he could bend his knee almost immediately. Pictured: File photo of an X-ray showing a total knee replacement

The pain was shocking. I was only allowed opioids every four hours and I’d be sitting in the hospital bed rocking backwards and forwards waiting for the next dose while trying not to scream in agony. And I have a pretty high pain threshold.

The two experiences could not have been more different; the implant was much more effective than I appreciated at the time.

THE SURGEON

Professor Hemant Pandit is a consultant orthopaedic surgeon at Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust.

Around 100,000 people a year undergo a total knee replacement on the NHS.

It can be a life-changing procedure for many with painful osteoarthritis (age-related wear and tear on the joints).

But it is also major surgery that can result in significant post-operative pain, potentially prolonging recovery time.

One of the main groups of pain-relieving drugs used afterwards is opioids, such as morphine and tramadol.

These are powerful medicines but are associated with a range of side-effects, from nausea and constipation to severe breathing problems and even dependence on them.

Around 100,000 people a year undergo a total knee replacement on the NHS. Pictured: File photo

Some patients can become addicted to the drug, even after just a few days.

Research shows between 50 and 80 per cent of patients on opioids suffer at least one side-effect – and a 2015 paper in the BMJ showed that just one week on the drugs increased the risk of patients becoming dependent on them by 20 per cent.

As a result, doctors usually only prescribe opioids for the first few days immediately after knee surgery, when the pain is at its worst.

After that, it’s mostly over-the-counter paracetamol or ibuprofen. And these can prove to be not strong enough for some people.

The wafer-style implant, called ATX-101, has been developed to provide round-the-clock pain relief during the first three to four weeks after surgery, when it’s vital that patients get mobile again and start to use the new knee as much as possible to improve the chances of a full recovery.

It’s made from the same material as in dissolvable stitches and is about the size of a 20p coin. Inside each wafer (the patient has two or three, depending on the dose required) is 500mg of bupivacaine, a local anaesthetic that is widely used in dental procedures and childbirth.

The wafer is designed to break down at such a rate that it releases larger amounts of the drug in the first few days after the surgery and then smaller amounts as the weeks continue. The whole thing dissolves eventually – after about one month or so.

The procedure we follow is a standard knee replacement operation. Under a general anaesthetic, we make a 10cm vertical incision on the front of the knee, remove the affected bones of the joint and put in the artificial joint, made of metal and plastic, using bone cement to fix it in place.

During trials of the new medication, most wafer patients were able to walk, get up and down stairs and climb in and out of their car sooner than those in the placebo group. Pictured: File photo

Once that’s secured, we stitch two of the ‘wafers’ to the tissue at the top of the kneecap and close the wound – the whole thing taking just over one hour.

During the study (involving 112 patients from the UK, Canada and Australia) 16 per cent of those given the highest dose of bupivacaine (1,500mg) needed no opioids during their recovery from knee surgery, compared to 3 per cent in those who did not get it.

The trial is testing two doses of the drug against one placebo group that was not given any bupivacaine.

Most wafer patients were also able to walk, get up and down stairs and climb in and out of their car sooner than those in the placebo group.

This could signal a significant step forward in pain control as about 50 per cent of patients who have a total knee replacement complain of severe pain after their surgery.