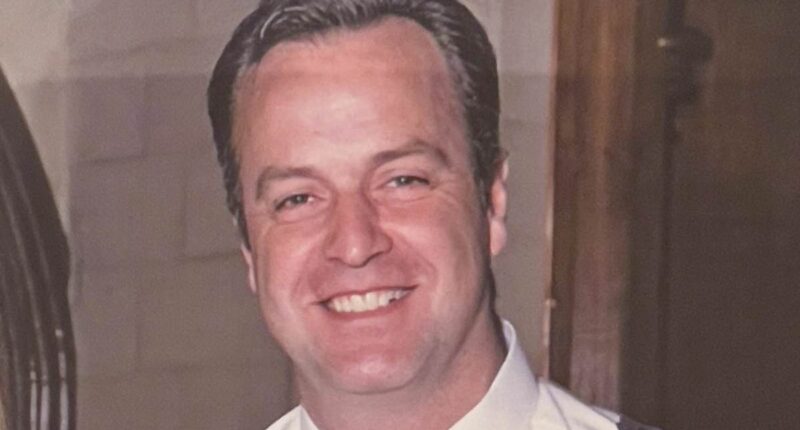

A retired police constable named Tim Bradshaw enjoys a sunny spring morning walk along the promenade in Bognor Regis. No longer in uniform, he is still easily recognized and well-liked by the locals. Even someone with a past as an ex-convict and heavily tattooed nods approvingly as Bradshaw walks by.

As Bradshaw nears the bandstand, an elderly man points him out to his friend, mentioning how Bradshaw apprehended some troublemaking youths on an electric bicycle. The elderly man’s friend agrees, showing support for Bradshaw. Many residents of the south coast town of Bognor Regis believe that Bradshaw, aged 55, should be commended for his actions.

Despite gaining some fame for his brave act on November 3, 2022, and receiving praise from the local community and beyond, Sussex Police had a differing opinion of Bradshaw’s actions.

No matter that Mason McGarry and Dominic Mizzi, the ‘feral’ pair whose e-bike Mr Bradshaw nudged with his patrol car, had terrorised his town. No matter that after they were taken down the crime rate dipped.

What seemed to matter to Sussex Police was teaching their award-winning, uncommonly dedicated officer a lesson. They did so without seeming much interested in his explanation for what happened.

If they had asked he would have said he used ‘tactical contact’ to prevent McGarry and Mizzi, who hit speeds of more than 50mph during the chase, endangering their own lives and those of the public.

The decision to prosecute him, says Mr Bradshaw, was made within minutes. Yet the case would hang over him, slowly corroding his passion for policing, for more than two years.

Eventually he was charged with causing serious injury by dangerous driving and faced a possible jail sentence. Yet after a five-day trial at Portsmouth Crown Court, a jury made its feelings on the case abundantly clear by taking just 20 minutes to acquit him – much, one imagines, to the chagrin of Sussex Police.

‘Thank you very much indeed,’ said the judge. ‘You will realise that was an important case, not only for this defendant but throughout the country.’

Indeed it was. As everyone knows, the invasion of our urban areas by electric bikes and scooters is a scourge of our times.

Perhaps, as many hope, Mr Bradshaw’s victory might encourage other officers to be equally robust when confronting them.

When the verdict was delivered the former constable felt a wash of release flow through him. His wife and son were in tears. So too was his union representative. Friends and colleagues all told him the same thing – that good sense had prevailed.

Sadly it came too late to salvage his career. Mr Bradshaw is a tough, resilient man but the stress of the case forced him to take early retirement last year.

‘I no longer exist in the eyes of Sussex Police,’ he says. ‘I was PC 16804. That’s all I was to them, just a number.’

What a way to treat a hero, came the collective refrain from the people of Bognor. And the town needs its heroes, now more than ever. Particularly when the likes of McGarry, who has more than 40 convictions, and Mizzi, who has 26, continue to behave with impunity. Every town has them, of course, swaggering young men who view the justice system with abject disdain.

And while Bognor Regis is known for being the sunniest place in Britain, few know its darker side better than Mr Bradshaw.

A sturdy 6ft 3in, he greets everyone with a smile and a cheery word. In many ways he typifies the old-fashioned beat policeman, or at least an approximation of one. For as Mr Bradshaw laments, they don’t exist these days. He wishes he could have been one.

Instead, during his 22 years fighting crime in Bognor, where he grew up, he made a point of stopping his Ford Focus patrol car as frequently as possible to talk to shopkeepers, nightclub bouncers, business owners, criminals, everyone and anyone.

Nurturing relationships and developing intelligence, he says, is a ‘lost art’ but always got him results. ‘Most officers couldn’t care less about this side of the job,’ he says. ‘They turn up for work, put their uniform on, switch their radio on, sit in briefing, wait to be told what to do and where to go, come back to the police station, have a cup of tea and wait for the next job.’

Mr Bradshaw was what he calls a ‘proactive’ officer who pursued leads without being ordered to do so. In his black notebook – ‘my bible’ – he assiduously jotted down all sorts of details that might prove useful. Names, number plates, dates of birth.

Instead of loafing in the police canteen between jobs, he conducted research, anything that might assist his work. And he developed a ‘copper’s nose’ – a willingness to act on instinct that, he said, his superiors discouraged. Mr Bradshaw paints a bleak portrait of modern policing. To many officers, he says, his story will be familiar.

He speaks of naive enthusiasm at the start of his career, a determination to do good, to lock up villains, then the crushing realisation that policing is far from straightforward – that you must battle not just the criminals but those above you. Fear of outside criticism, he says, often from single-interest groups, infects decision-making at the top. ‘There is the great obsession with how we are perceived,’ he says. It also percolates to the front line.

‘Officers are always looking over their shoulders, terrified of doing or saying the wrong thing,’ says Mr Bradshaw. ‘It makes them reluctant to think on their feet and be hands-on.

‘Nowadays the police don’t necessarily recruit those best suited to the job. The hope is that they grow into the job. But many of them don’t want to get out of the patrol car, they go from job to job with blinkers on.’

When the e-bike menace hit Bognor a few years ago, Mr Bradshaw was there to confront it, not in a comfy office or control room, but on the front line.

The bikes quickly became the preferred transport of the town’s most prolific young criminals – those who thought nothing of scaring old ladies witless by mounting the pavement and snatching their handbags.

County lines gangs made use of the bikes to move and distribute drugs. And night after night, balaclava-clad yobs goaded police into chasing them.

‘It was a game to them,’ says Mr Bradshaw. Often they would sidle silently alongside a patrol car, kick its doors and taunt officers with rude hand gestures. ‘It was impossible to catch them because they knew all the alleyways we couldn’t go down, all the nooks and crannies,’ he says.

The bikes can now be ridden on roads without needing a licence or a number plate. Often they are modified by their owners and are able to hit speeds of up to 60mph, even though the official limit is 15.5mph.

Depressingly, the likelihood is that even if caught, they would face little in the way of sanction. Mr Bradshaw says ‘a notion has crept into policing that we shouldn’t punish juveniles.

‘But if you are criminally responsible for what you do then you should face the consequences. If you repeatedly offend and never get punished, what message does that send out?’ Punishment for young offenders all too often now means a referral to the youth offending team. In other words sitting him down and having a chat. That’s the punishment. A chat.’

McGarry was 16 at the time of the e-bike incident though Mr Bradshaw says his offending started around the age of ten. From shoplifting he graduated to criminal damage, chiefly throwing objects at people from the roof of a shopping centre.

‘He wasn’t punished,’ says Mr Bradshaw. ‘Worse, social services rewarded his bad behaviour by giving him a new pair of trainers because he didn’t like the ones he had, and giving him a new PlayStation and taking him to McDonald’s. It was all so pathetically weak.

‘As he got older his criminality escalated. He beat up Eastern Europeans, who for some reason he disliked. He is a calculating, manipulative individual who doesn’t give a damn about anyone else. His attitude to the law can be summed up as, ‘Arrest me then. So what’. Mizzi also had numerous convictions, including assaulting emergency workers.

‘A few weeks before the tactical contact he’d broken his hip, pelvis and leg in an e-bike crash. A pedestrian was involved. And the previous month one of his friends had died in a motorbike accident. This was the background to why I acted as I did.’

And it is worth noting too that Sussex Police had previously authorised tactical contact on three occasions… On the night of the incident, McGarry and his pillion Mizzi, 22, ‘appeared suddenly’ undertaking Mr Bradshaw’s patrol car at speed on a narrow road and ‘making the usual hand gestures’.

He says: ‘An opportunity presented itself and I tapped them from behind. It was suggested that I acted out of anger – absolute rubbish.

‘McGarry sprinted off but I explained to Mizzi as he lay groaning at the roadside that I did it to stop them endangering their own lives and those of the public. Genuine reasons.

‘He admitted that he was in pain not from what had just happened but from his injuries from his previous crash. A very small glimmer of remorse crossed his face –

but it didn’t last.’ Beyond their immediate families, few, of course, would sympathise with McGarry and Mizzi. Certainly not the family of Sakine Cihan, 56, who was knocked down and killed in London by a rider travelling at 30mph.

Or Jim Blackwood’s family. He was the 91-year-old Army veteran from Rochester, Kent, killed when an e-bike rider struck him as he put his bins out.

Or the parents of Carter Ralph, ten, who was left with ‘his nose hanging off’ after being sent flying by an e-bike that being ridden on the pavement in Loughborough, Leicestershire, last October.

Mr Bradshaw, who now drives a bus for a living, speaks of a depressing postscript to his story.

Last week he spotted McGarry up to his old tricks, this time chasing a terrified 16-year-old boy down a street. He says: ‘The lad jumped on to my bus as I was parked in the station, and I got up and stood on the steps to stop McGarry getting on.

‘He looked at me all cocky and arrogant, telling everyone on board that I’d knocked him down but that he had taken my job.

‘He threatened my family. Then he took a big spliff out of his mouth and blew smoke in my face. I said, ‘Go away Mason and take your cannabis with you’. Then he lunged at me. He was joined by his mate in a balaclava who was threatening to stab another bus driver. Of course no action was taken against them.’

As he tells this story, sitting in a restaurant in the town centre, someone else recognises him. This time thankfully it’s a friendly face and the two exchange pleasantries.

Before he leaves, Mr Bradshaw says: ‘I fear nothing will change until there’s a shift in direction from the very top. That means ensuring there are enough experienced officers to help younger colleagues find their way. It means ending the ideology of box-ticking. And it means empowering the police to be robust and hands-on.

‘This is the only way we are going to tackle the huge problem that illegal e-bikes are causing all over our country. If we don’t grasp this reality then the unscrupulous criminals causing chaos will keep running rings around us.’

Sussex Police said officers were ‘aware of the impact illegal and anti-social riding of e-bikes and e-scooters has… and have carried out proactive operations dedicated to tackling the issue.’

It added: ‘Our officers are faced with difficult situations on a daily basis, and we do not underestimate the strength and bravery they show in making split-second decisions.

‘We police by consent so it is right that our actions are scrutinised, particularly where there is an incident that has resulted in injury.’