Since the intense nuclear weapons competition between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Cold War, humanity has possessed the terrifying ability to eliminate itself in a catastrophic nuclear inferno.

Despite several international agreements to limit arms proliferation, the US and Russia, the two most heavily armed nations, still maintain thousands of nuclear warheads, more than sufficient for complete mutual destruction.

If a major nuclear attack were launched by any country, its adversaries would likely respond with their own destructive arsenal, leading to widespread devastation from nuclear fallout worldwide.

But Vladimir Putin’s decision to hit Ukraine with a never-before-seen hypersonic, nuclear-capable missile last month forced world leaders and military chiefs to confront a new possibility – that of a single, well-placed strike on a target in the West or one of its allies.

Though early warning systems would hopefully detect a missile launch directed at the West, giving defensive networks a chance to intercept, there remains a scenario in which a major Western city could suffer an isolated attack.

With the help of a model produced by Alex Wellerstein, a professor and historian of nuclear technology, MailOnline examines the devastating effect of a single Russian Topol-M SS-27 ICBM if detonated above some of Europe and America’s major population centres.

The Topol is by no means Russia’s most devastating nuclear weapon – the likes of the RS-36 ‘Satan’ ICBM carries multiple warheads each with a yield orders of magnitude greater.

But the modern Topol missile’s warhead still comes with an estimated yield of roughly 800 kilotons – more than 50 times the power of the first atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945.

Topol-M intercontinental ballistic missile test-launched from a missile silo at Plesetsk Cosmodrome

In the event of a large-scale nuclear launch from any state, its foes would almost certainly let loose their own doomsday machines, turning much of the globe into a nuclear wasteland

Topol-M missile at a Victory Day parade in Moscow, Russia

The following estimations of casualty figures and damage reports are based on the event of a Topol-M 800-kiloton warhead exploding a few hundred feet above the ground.

The figures do not take into account the untold numbers of people who would perish following days, weeks or months of the blast from the effects of acute radiation sickness amid the radioactive fallout, lack of access to food, water, power, medical care and other basic services.

Western Europe

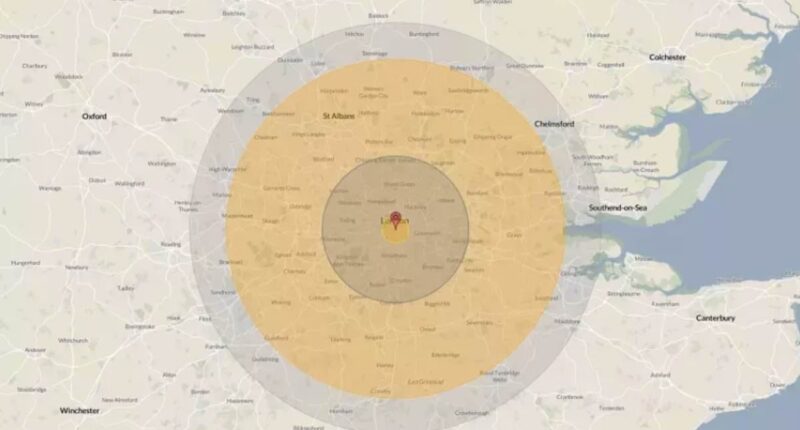

London, Westminster

As the explosion forms a towering mushroom cloud in the air, fires would spread over a large area, even putting people in underground shelters at risk of carbon monoxide poisoning.

Anyone within three square kilometres of the detonation of the Topol is instantly vaporised by a towering fireball as hot as the sun (inner yellow ring).

The Houses of Parliament, Buckingham Palace, Westminster Abbey and Trafalgar Square are completely and utterly destroyed.

Within a fraction of a second, the heat would cause a high-pressure shockwave to spread out from the blast, tearing through buildings with powerful force at supersonic speed.

Anyone living within 134sq km – as far away as Wandsworth, Camden and Hackney – is almost certainly wiped out due to horrific injuries and total body burns amid widespread destruction of buildings and infrastructure (inner grey ring).

Large numbers of people living as far out as Stratford, Chiswick, Lewisham and Wimbledon are liable to suffer third-degree burns and buildings as far as Kingston, Croydon and Ilford suffer significant damage.

Wellerstein’s model predicts that almost 1 million people would be killed instantly, with 2.2 million more suffering severe injuries, many of which would likely lead to death.

Paris

Casualties in the French capital would likely be even worse.

Some 1.5 million are expected to be killed immediately by the blast, with the toll of injured rising to 2.7 million.

A Topol detonated over central Paris wipes the Eiffel Tower and the Palais de Chaillot off the map, with the world-famous Arc de Triomphe, the Louvre and Montparnasse Tower reduced to rubble.

Residents are far out as the suburbs of Saint-Denis suffer third-degree burns, and the windows of Paris Orly airport some 15km south of the Eiffel Tower would be shattered by the shockwave.

Amsterdam

The Dutch capital is less densely populated than London and Paris, meaning casualty figures are lower.

But Amsterdam’s comparatively small size means much of the city is wiped out.

Roughly 370,000 people are killed in the moments following the blast with more than 530,000 expected to sustain severe injuries.

The city centre and the nearby port are totally demolished with buildings in the neighbouring city of Haarlem suffering damage from the shockwave.

Rome

The Topol leaves some 770,000 inhabitants dead in Rome, with more than 1 million suffering grievous harm.

The Italian capital’s treasured Colosseum crumbles to dust along with the Pantheon and much of Rome’s Old Town.

A few kilometres from the epicentre of the blast, the Vatican also suffers massive damage with most of its inhabitants likely killed.

The shockwave of the explosion continues outward, wreaking havoc and shattering windows as far as the town of Dragona, just a few kilometres from the shore of the Mediterranean.

Central Europe

Berlin

Almost 640,000 people perish within moments of the blast over central Berlin, with almost double – 1.2 million – left with brutal injuries.

The Brandenburg Gate, Berlin cathedral, the instantly recognisable TV tower spire and the Reichstag – Germany’s Parliament building – are pulverised.

People living as far as the suburbs of Spandau and Wilhelmstadt suffer significant burns and the punishing shockwave affects buildings on the outskirts of the city of Potsdam several dozen kilometres south west.

Warsaw

Some 615,000 people in Warsaw are eliminated by the Topol-M airburst and the raging fireball with another 750,000 sustaining injuries.

Most of Warsaw’s old town as well as its burgeoning financial and business centre are wiped out.

The Royal Castle is razed to the ground along with the Warsaw local history museum, with the brutal shockwaves reaching as far as the outskirts of the Kampinoski National Park nearly 20km away.

Nordics

Helsinki

In the more sparsely populated Finnish capital on the banks of the Gulf of Finland, a Topol-M blast causes the deaths of more than 120,000 and deals savage injuries to roughly 300,000 more.

Several islands of the archipelago on which the capital is built are devastated, while Helsinki airport some 16kms inland is hit by the shockwave and sustains some damage.

Stockholm

In the Swedish capital, the death is toll more than twice that of Helsinki, standing at 268,000, while the number of injured rises to 500,000.

Stockholm’s archipelago is also more densely concentrated than Helsinki, meaning more vital architecture and infrastructure are laid to waste.

The Swedish Royal Palace, Stockholm City Hall and the Vasa Museum are all eviscerated with the blast radius stretching out to Danderyd, Djursholm, Huddinge and Boo.

US

Washington DC

A Topol-M strike at the heart of the American political capital erases several landmarks and locations synonymous with US history and politics.

The White House and the Capitol building are demolished along with the instantly recognisable Washington Monument, the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, the National Air and Space Museum and the National Archives.

Estimated fatalities rack up to 485,000 with another 839,000 suffering severe injuries.

People living as far as Alexandria and Bethesda are hit with third-degree burns, with the shockwave extending out far beyond Silver Spring and College Park.

New York

An airburst over central New York unsurprisingly would have catastrophic consequences given the population density and massive infrastructure.

The immediate fireball vaporises almost everyone in Soho, Little Italy, the Lower East Side, East Village and West Village, with the eruption levelling buildings and slaying people in Midtown, Long Island, Williamsburg, Brooklyn and the Upper East Side, as well as those across the river in Jersey City and Hoboken.

People in Harlem, Bushwick and North Bergen are dealt third-degree burns, with the shockwave extending as far as the Bronx and toward the outskirts of Yonkers.

Some 1,560,000 are killed with the number of injured almost reaching 3,000,000.

The Topol-M is by no means the most powerful nuke in Russia’s arsenal.

But even a 500-kiloton nuclear bomb – almost half as powerful as the Topol-M – would still raze buildings and kill nearly 100 per cent of those within half a mile of the epicentre of the blast.

If dropped on Westminster, that would mean the Houses of Parliament, Downing Street, St Thomas’s Hospital and Westminster Abbey being completely obliterated by the thermal blast.

‘That blast wave will keep rolling – it will drop off severely, but it will keep going – destroying buildings and causing casualties out until about two and a half miles,’ Dr Jeffrey Lewis, a professor at the Middlebury Institute, told MailOnline.

In London, that encompasses the Tower of London and Battersea Power Station. Most of Hyde Park, half of Regent’s Park, Chelsea, Knightsbridge and Belgravia. The damage would span from Camden to Brixton.

The Royal Albert Hall, Barbican and the Bank of England would likely collapse in the strike.

Fires would rage and emergency services outside of the capital would be stifled by collapsing infrastructure and piles of rubble up to 30ft deep.

A direct strike on the centre would see a ‘likely fatal’ ring of radiation stretching as far as the easternmost part of Hyde Park, with most buildings collapsing in the City and around the Kensington and Chelsea areas.

Beyond that, residents in Camden, Islington, Tower Hamlets, Lambeth and Wandsworth would suffer third-degree burns.

And six miles away, from Chiswick to Stratford, residents would likely suffer injuries as the blast shatters windows and causes damage to houses.

Those able to shelter inside a building, ideally ducking under a desk or into a cupboard in case the ceiling collapses, stand a better chance of surviving – but the shockwave at this distance could still be fatal.

While the fatal ring of radiation is limited to the very heart of the city, its effects could spread beyond the M25 depending on the weather, stifling the victims’ ability to produce natural defences against infection.

Those affected would feel nausea as exposure damaged blood vessels and bone marrow, weakening the body’s ability to produce white blood cells needed to fight infection.

As the body starts to decay, victims are left vulnerable to outside infections and internal haemorrhaging.

In a densely populated city like London, a 500kt blast could foreseeably kill as many as 400,000 people in an instant. But more than 850,000 could also sustain injuries from the blast, shockwave and radiation.

With much of London’s infrastructure taken out, it would likely be hospitals and fire departments in the capital’s suburban sprawl that take on responsibility for treating casualties, putting unprecedented pressure on local services.

But ‘all of the dedicated burn beds around the world would be insufficient to care for the survivors of a single nuclear bomb on any city,’ warns the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons.

The fatalities would invite pests and disease, spreading illness further around a population already decimated by compromised immune systems and creating new epidemics.

Significant strikes – nuclear or otherwise – on large population centres would also stifle business, causing huge supply chain disruptions in Britain and beyond. At home and overseas, livelihoods reliant on trade with London would be disrupted or destroyed even if they escaped the physical effects of a blast.

And with communication networks likely knocked offline, the response to dealing with plague, injury and demolition would be slow and awkward.

A mushroom cloud rises after the so-called Tsar Bomba was detonated in a test over the remote Novaya Zemlya archipelago in USSR, in this still image from previously classified footage taken in October 1961

The fireball created by the Tsar Bomba, the most powerful nuclear weapon ever tested

Russian Topol M intercontinental ballistic missile launcher rolls along Red Square during the Victory Day military parade to celebrate 72 years since the end of WWII and the defeat of Nazi Germany, in Moscow, Russia on May 9, 2017

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, both destroyed by American atom bombs in 1945, show how communities can rebuild cities from the ground up after their total destruction.

The bomb that hit Nagasaki caused ground temperatures to reach 4000C and radioactive rain to fall over the beleaguered survivors.

Ninety per cent of physicians and nurses were killed in Hiroshima and 42 of 45 hospitals were rendered non-functional.

Even as survivors were moved on and rebuilding efforts commenced, within five to six years the victims began reporting a higher incidence of blood, thyroid, breast and lung cancers.

Pregnant women experienced higher rates of miscarriage and infant mortality, scarring the next generation and stultifying hopes for the future.

Britain is fortunate to be among the countries with preparations in place to stop an incoming attack. But experts warn the defences are not comprehensive and could be easily overwhelmed.

But it is not only the nuclear threat that poses a direct challenge to Britain’s defences, experts warn. The war in Ukraine has shown the urgency of anti-missile defence systems – and the UK has long left itself exposed to all manner of attacks from above.

‘There are some basic things we need to do in this country and we are failing on all of them,’ Edward Lucas, a security expert and politician, tells MailOnline. ‘We were not properly equipped during the Cold War’ and since then have retired many of the tools used to prepare the public and avoid the nuclear threat.

In Britain, RAF Menwith Hill, near Harrogate, stations the site for the European Relay Grounds Station, which picks up information from the American Space Based Infra Red System (SBIRS) satellite system.

RAF Fylingdales, on Britain’s east coast, also shares information with the US and tries to calculate the trajectories of incoming missiles, allowing interceptors to knock them out.

The moment Russia used the Oreshnik hypersonic missile for the first time to strike Dnipro, on November 21

In the event of a missile launch, it is unlikely an adversary would fire just the one rocket, however, meaning Britain’s ‘means of destroying missiles will only be able to deal with a limited ballistic missile threat’, according to a 2003 Ministry of Defence White Paper.

At the time, barely a decade after Britain retired its Cold War bunkers, air raid sirens and public warning systems, the government warned of the ‘immediate state threat’ of Iraq but assessed that there was ‘no immediately significant ballistic missile threat to the UK’.

Edward Lucas told MailOnline that while London likely would be protected by anti-missile defence systems, ‘we have given up on anti-missile defences in this country’.

An alert from SBIRS would likely see the UK move its Type 45 destroyers to the English Channel and Thames Estuary in order to cut off incoming missiles before they land. This would make London one of the best-guarded places in the British Isles.

But Britain only has six Type 45 destroyers, each equipped with Sea Viper missiles able to knock out up to 16 targets mid-air, from some 70 miles away. Each volley could in principle knock 420 nuclear weapons out of the sky by those figures. Russia alone has an estimated 5,580.

The Type 45s are Britain’s only defence against Russian multi-missile attacks, the former head of the UK Armed Forces, General Sir Nick Carter, warned MPs last year. And while Ukraine has shown ‘how important it is’ to have strong stockpiles of anti-missile defences, Mr Lucas says, Britain finds itself desperately lacking.

Destroyers represent Britain’s best anti-missile defences, he says, but continued success would come to depend on the American ability to continue resupplying the Navy.

In World War II, Britain was able to manufacture plenty of low-tech defences against incoming attacks. Today, there is no equivalent to the American Patriot System, or the Israeli Iron Dome, able to prevent repeated attacks from incoming missiles.

Sir Nick Carter, former Chief of the Defence Staff, told MPs last June that ‘the extent to which we’ve got a counter-missile system is debatable,’ suggesting the only system comparable to Patriot was the Type 45s.