The horrors of Syria’s Bashar Al-Assad are finally being laid bare.

After ruling the country with brutality for five decades, the family’s oppressive regime was brought to an end on Sunday. Rebel forces managed to defeat regime soldiers and free a vast network of prisons, exposing one of the most heinous state-sponsored torture systems in modern history.

Nearly 160,000 people have disappeared into Assad’s hellholes since the Syrian uprising of 2011.

Sam Goodwin is the only American civilian ever to be detained in one of these prisons – and released.

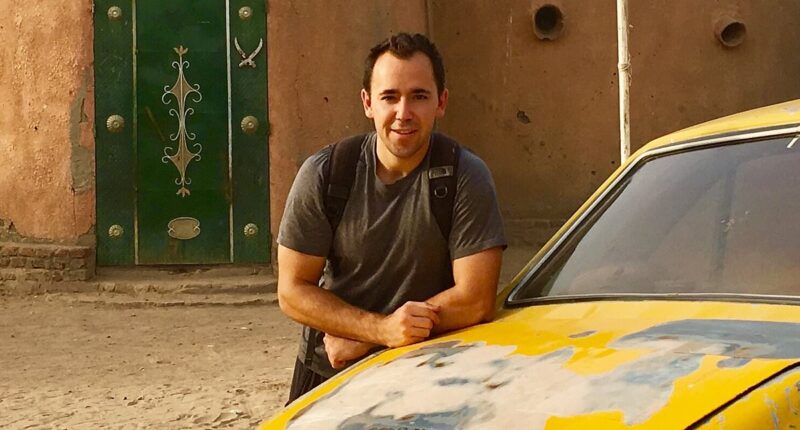

During his travels around the world, Goodwin, who was 30 years old at the time, was abducted by Assad’s forces on May 25, 2019, while in Qamishli, northeast Syria. He endured 63 days of captivity in the hands of his captors, far from his hometown of St. Louis, Missouri.

Today, Goodwin, the writer of ‘Saving Sam: The True Story of an American’s Disappearance in Syria and His Family’s Extraordinary Fight to Bring Him Home,’ reveals the shocking truth about the atrocities that took place within Assad’s brutal prisons.

It’s impossible to forget the sounds of another man’s torture.

Every day, twice a day, a prison guard would walk down the halls of the Damascus dungeon where I was being held, opening cell doors one by one.

I’d hear the distant clank of a metal bolt being pulled back, a second later, the thud of a club, a frantic bout of screaming for about thirty seconds, then silence.

Next came the bang of a second deadbolt and more awful thrashing and shouts.

Nearly 160,000 people disappeared into Assad’s hellholes since the Syrian uprising of 2011. Sam Goodwin (pictured in Chad) is the only American civilian ever to be detained in one of these prisons – and released.

Five-decades of his family’s savage rule came to an end on Sunday when rebel forces liberated an extensive network of prisons revealing one of the most depraved systems of state-sponsored torture in modern history. (Pictured: man holds up bloody rope at Sednaya Prisonon December 9, 2024).

This went on, cell by cell, as the guards worked their way toward me, opening each door and beating the hell out of each inmate.

As the guards got closer and closer to my cell, I could hear the creak of the door hinges and the thud of batons on flesh.

I didn’t know what fear was until I heard a grown man crying for his life. Some of the prisoners were women and children.

I would sit on the filthy concrete floor of my tiny room, back to the wall, too frightened to move, my knees pulled up to my chest, my arms around my legs, my mind a blank slate of anticipation. The screaming, so close, it was unbearable.

It was beyond terrifying, in part because I couldn’t actually see anything.

For all 27 days that I spent in solitary confinement inside the Branch 215 detention center of the Syrian penitentiary system, I never saw another inmate. I only heard their screams.

I’d later come to learn the purpose of Branch 215: it is a place to break political prisoners – destroy human beings. Ordinary Syrians nicknamed it the ‘Branch of Death.’

When the bolt on my cell would slide back, a large, older man would loom in the doorway. He always wore a green military-style uniform and a forage cap on his head. His minions always behind him, their faces as expressionless as his.

On our first meeting, I was transfixed by the man, who stood for a long moment, staring at me. He gave a half wave from his temple, almost a casual salute, and said, ‘Samwell.’

I may have managed to croak out a feeble ‘yes’ before he turned on his heel and left. The deadbolt slid into place. The door of my other neighbor’s cell groaned open and the beatings continued.

I couldn’t help but wonder when my turn for a beating was coming. But it never came. I’ll never know why.

My room was less than ten steps long by four steps across. It had a hole in the corner of the concrete floor that reeked of sewage. Once a day I was fed bread, boiled potatoes and water – and given a single blanket to sleep.

I would sit on the filthy concrete floor of my tiny room, back to the wall, too frightened to move, my knees pulled up to my chest, my arms around my legs, my mind a blank slate of anticipation. (Pictured: Sednaya prison)

After two weeks in Adra, I was struck by how kind most of the inmates were to me. One of them explained why. ‘Sam,’ he said, ‘in Syria, all the good people are in prison because all the bad people are on the outside putting us in here.’ (Pictured: Sednaya Prison)

On Day 23, guards rushed into my room. I was roughly handcuffed, blindfolded and tied to a chair.

‘Sam, if you don’t start telling the truth, I will hand you over to ISIS!’ a questioner screamed – again and again – in a thick Middle Eastern accent.

They accused me of being an American spy and a terrorist collaborator, which really meant someone who sympathized with Syrian rebels that had revolted against Assad in the wake of the Arab Spring in 2010.

I was neither of these things. But I was terrified and utterly helpless. I tried to explain that I was simply a traveler, not a secret agent or a revolutionary.

For that I was thrown back in solitary.

On Day 27, I was dragged from my cell and transferred to Adra prison on the outskirts of Damascus, where I would remain for a further 36 days. Adra is one of the prisons that Syrian rebels have now liberated. Videos of their celebrations inside its wall are circulating on social media.

In Adra, I was put in a cell with about 40 men, where I learned that virtually all of them were not criminals. Most were being held on ‘terrorism’ charges, a blanket charge given to anyone who had taken part in anti-government protests.

I befriended a 80-year-old man who was convicted of being a ‘sniper,’ but it was plain to everyone that he was blind.

After two weeks in Adra, I was struck by how kind most of the inmates were to me. One of them explained why. ‘Sam,’ he said, ‘in Syria, all the good people are in prison because all the bad people are on the outside putting us in here.’

These men told me horror stories of their time inside Assad’s gulags.

One prisoner recounted how while in Branch 248 the guards burned his genitals with a blowtorch to extract a false confession.

Another explained the vile ways some inmates were executed. In the most notorious prison named Sednaya, north of Damascus, guards killed severely malnourished prisoners by laying them on concrete floors and crushing them to death under their boots.

One of my closest friends from Adra prison is a man I’ll call Arthur. He was in Sednaya before being transferred to Adra. He won’t say much of his time here, but he has revealed some details.

Arthur spent 22 days in a subterranean level of the prison, where he knew not to look any of the guards in the eyes. For that he would have been executed.

While he was there, he suffered a near-debilitating case of diarrhea, though he knew not to ask for medicine. For that he also would have been killed.

Amnesty International called Sednaya a ‘human slaughterhouse.’ Human rights groups say tens of thousands of inmates were detained there.

There are reports of systematic sexual assaults, the cutting off of ears and genitals, prisoners forced to rape or even kill each other – and the use of cremation to hide the bodies.

One video out of Sednaya claims to show a giant iron hydraulic press that may have been used to crush prisoners to death.

It’s difficult for me to doubt any of it.

One video out of Sednaya claims to show a giant iron hydraulic press inside that may have been used to crush prisoners to death. (Pictured: Iron press in Sednaya prison)

Every day, twice a day, a prison guard would walk down the halls of the Damascus dungeon where I was being held, opening cell doors one by one. (Pictured: Rebels liberate Sednaya prison).

Throughout my detainment, I never knew what would happen to me, if I’d ever be released, see the sky again or my family.

But, on the morning July 26, 2019, I was suddenly ushered out of Adra and driven to Lebanon.

Unbeknownst to me, my family had managed to reach the Lebanese government, which mediated my release.

Now that the Assad regime has fallen, I believe a brighter future is ahead for Syria and its people.

However, there is at least one American citizen still missing there. His name is Austin Tice and he is a hero who bravely travelled there over a decade ago to expose the horrors of the Syrian revolution to the world.

I never encountered Austin while in captivity, but I pray he is safe. And I hope that he will soon be reunited with his parents, as I have.

![Anne Burrell: Food Network Chef Found Dead Near Dozens of Pills [Report]](https://bbcgossip.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/Anne-Burrell-Food-Network-Chef-Found-Dead-Near-Dozens-of-380x200.jpg)