Our local ironmonger is shutting down this week, marking the end of a service that has been around for more than a century. This shop, located in the market town of Heathfield, has been a go-to destination for us for a quarter of that time.

Established in 1919 by three individuals with a shared vision of community service, Heathfield Ironmongers offered a wide range of products for the home and garden, starting from a simple nail. Their website, now inactive, highlighted their mission to cater to the community.

The decision to close the shop was influenced by a combination of factors, according to the current manager who my wife spoke to. While the disappearance of banks in the area and the impact of Covid played a role, the main reason cited was the government’s choice to reduce relief on business rates for retailers and increase employers’ national insurance contributions, which was described as the final blow.

Fractured

This is far from the only independent shop on our small High Street to have closed in the past few weeks. Others include Wanted on Voyage, which sold travel items, from suitcases to board games; Kiln Home, where we shopped for Christmas presents only last month, and the hairdresser I used opposite Sainsbury’s – which has warned it would be shedding 3,000 jobs nationally.

The weekend’s announcement from WHSmith that it was putting the for sale sign on all its High Street stores is the latest indication of British retailers’ assessment of Rachel Reeves’ Budget.

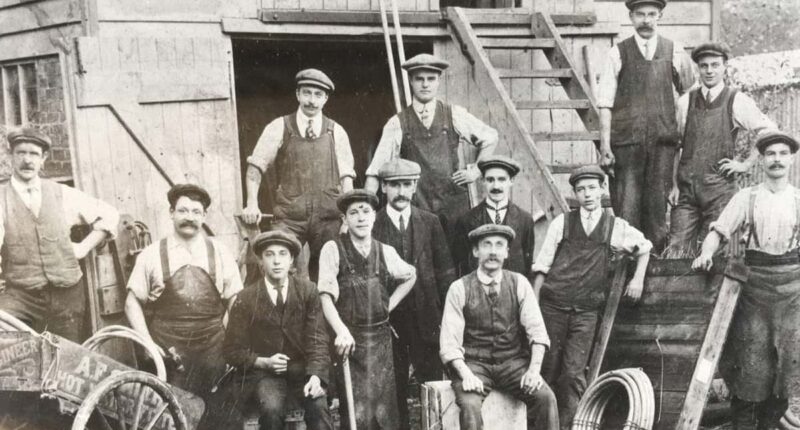

Heathfield Ironmongers, where you could buy almost everything you needed for home or garden, was founded in 1919

The shop had seven managers in its lifetime with the first being Mr William Phillips who ran the store from 1919 to 1974

And if well-resourced firms such as Sainsbury’s and WHSmith are feeling like that, imagine how much more difficult it is for small, independent High Street stores without the same economies of scale.

For them – and for us, their customers – this represents a staggering betrayal by Sir Keir Starmer, his Chancellor, and the Deputy Prime Minister, Angela Rayner. During the general election they all proclaimed to local newspapers how they would revive our High Streets, especially because of the vital social role of small, independent family stores.

Rayner bemoaned how the decline of the High Street ‘after 14 years of the Tories’ had ‘fractured communities’ and that ‘rejuvenating our High Street is incredibly important… we all went with our nans or our mums and dads on the High Street and it meant so much’.

Meanwhile, her leader, in an article for the Bradford Telegraph & Argus, declared: ‘My Labour party is determined to work with local communities to breathe life back into our High Streets.’

Starmer also told us, during the election campaign: ‘Small businesses are the beating heart of our economy, our communities and our High Streets. Our Plan for Change will drive economic growth across the country so small businesses can thrive.’

There was no plan. Worse, Labour invented a ‘Tory black hole’ in the finances in order to justify the swingeing increase in taxes on businesses – the exact opposite of what was in their manifesto.

Heathfield Ironmongers (pictured in the 21st century) which was located at 108 High St in Heathfield, East Sussex

The ‘final nail’ in the coffin which led to Heathfield Ironmongers’ closure been Labour’s decision to reduce business rates relief for retailers and to raise employers’ national insurance. Pictured: Chancellor Rachel Reeves

This had promised to make the business-rates system less, not more, onerous because ‘the business tax regime matters for investors’, and ‘small firms, entrepreneurs and the self-employed face unique challenges’.

Now look: the Centre for Retail Research predicts about 17,350 shops will close in Britain this year, and most of those closures will be independent retailers (think of all those individual dreams and livelihoods destroyed).

Similar bleak forecasts have been produced by the commercial property group Altus, whose president Alex Probyn said: ‘Despite Labour’s manifesto recognition of the undue burden business rates place on our High Streets, the burden will be significantly increased.’ He described Labour’s decision to scale back business rates relief as ‘foolhardy’.

The sole growth on our High Streets is in cash-only operations, such as the extraordinary proliferation of Vietnamese nail bars: and as the Mail reported a week ago: ‘Crimes including money laundering and modern slavery are taking place ‘in plain sight’ on the High Street – with organised gangs using seemingly ordinary shops as fronts for their illicit empires.’

Mourned

So, well done, Sir Keir, former Director of Public Prosecutions. Not only is the betrayal of your election manifesto causing the closure of thousands of the traditional family stores that you pledged to preserve as ‘the beating heart of our communities’ – the gap they leave is increasingly being filled by money-laundering operations run by foreign gangsters.

And Angela Rayner’s proposed ‘reforms’ to increase employees’ rights will have precisely the opposite effect: they will further punish long-established independent High Street retailers, and thereby give more opportunities to enterprises operating outside the law and the tax system.

Anyway, I mourn the closure of Heathfield Ironmongers, opened in 1919 by ‘three like-minded men’ – and finished off by three like-minded politicians: Angela Rayner, Rachel Reeves and Keir Starmer.

Great storms are not man’s fault

Man’s nefarious industrial activities have predictably been blamed by, among others, ITV weatherman Chris Page, for the intensity of Storm Eowyn.

Actually, as Suzanne Gray, professor of meteorology at Reading University, said: ‘The observed trends in UK storminess have not provided a conclusive link with climate change.’

There has always been a tendency to blame alleged human wickedness for malign events in nature.

The most spectacular example in our island’s history forms the first chapter of Thomas Pakenham’s latest book, The Tree Hunters (Incidentally, it’s remarkable that he and his sister Antonia Fraser are both churning out fine volumes of history in their 90s.)

The Great Storm of 1703 caused devastation in just one 24 hour spell

Gusts in the English Channel topped 140mph, 300 Royal Navy ships moored on the South Coast were destroyed and at least 8,000 sailors lost their lives

As Thomas observed to me, the great storm of 1703 made even that of 1987 look piffling. Many millions of trees were felled, a grave problem for national security, as they were the source of timber from which our ships were made.

And the human loss was immense: about 300 Royal Navy ships moored on the South Coast were destroyed in the extratropical cyclone that struck on November 26, 1703. At least 8,000 sailors lost their lives – roughly a fifth of the seamen of the British fleet.

It was widely claimed that these meteorological events represented the judgment of God for the ‘crying sins of this nation’.

Though there were no reports of clerical fatalities when the lead roofing of Westminster Abbey was ripped off, the Bishop of Bath and Wells and his wife died when a chimney at the Bishop’s Palace crashed through their bedroom.

Anyway, let’s recall that this took place before the now stigmatised industrial revolution, when coal took over from wood as our main source of energy and our lives were transformed . . . for the better.