‘Whatever sentence you are about to receive… remember that after your days on earth are done, on your dying day, there will be no release for you.

‘The screams of Hell, Kyle, I can hear them faintly now. The red carpet will come out for you… your miserable fate will last for eternity.’

Concluding his victim impact statement during the sentencing of Kyle Clifford, who was convicted of murdering his wife and two daughters, BBC racing commentator John Hunt used powerful words.

They were extraordinary not just for their force, but for being so unexpected.

The existence of Hell is rarely discussed in public conversations nowadays, including church sermons and courtrooms.

The disappearance of Hell, even from religious settings, has been a long time in the making.

A Catholic individual remembers a priest from the 1960s named Father O’Sullivan, who emphasized the significance of acknowledging Hell by stating that the Devil benefits from its absence in discussions.

Damnation

The point being that the loss of the fear of eternal damnation was encouraging people to think they could get away with the behaviour that might, in that priest’s view, consign them permanently to the Netherworld.

Court artist sketch of John Hunt as he concluded his victim impact statement at the sentencing of Kyle Clifford. He said: ‘The screams of Hell, Kyle, I can hear them faintly now. The red carpet will come out for you… your miserable fate will last for eternity’

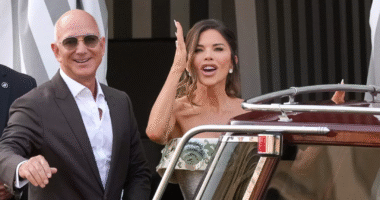

BBC racing commentator John Hunt with two of his daughters, Hannah (left) and Louise, who were both murdered by Kyle Clifford

Or, in more political terms: the rise in criminality and anti-social disorder is intimately linked with the decline of belief in the idea of supernaturally ordained retribution.

But to see that as causation rather than mere correlation is itself unfashionable, and even regarded as scandalous. I discovered this as long ago as April 1992, when, as Editor of the Spectator, I published an Easter piece by the Catholic Conservative MP John Patten in which he argued: ‘Fear of eternal damnation was a message reinforced through attendance at church every week. The loss of that fear has meant a critical motive has been lost to young people when they decide whether to be good citizens or to be criminals.’

This caused a sensation because in the period between the commissioning of the article and its publication, John Patten had been promoted to Secretary of State for Education by the then PM John Major.

As the Independent reported: ‘It was read with horror by much of the educational establishment.

‘I don’t know what planet that man comes from,’ one union official said.

‘I mean, what were my members meant to do? Tell little Johnny to knock it off, or he’ll go to Hell?’ ‘

In 1992, the Spectator published an Easter piece by MP John Patten in which he bemoaned the loss of the fear of eternal damnation

Another newspaper ran a sardonic leading article entitled ‘Hell: who needs it?’ Though of the huge amount of letters which Patten received following his intervention, the overwhelming majority were supportive.

Many of them, I imagine, were influenced by nostalgic thoughts of the immediate post-war era. Crime in the UK had risen from fewer than 500,000 recorded offences in 1950, to 5.3million a year when Patten wrote that article.

But you don’t have to be a Catholic, or even religious at all – and I am not – to recognise the constraining effects of a belief in divine punishment.

This was the theme of a remarkable book – God Is Watching You – published in 2016 by Professor Dominic Johnson of Oxford University.

Johnson, himself an atheist, drew on research from anthropology, evolutionary biology, experimental psychology and neuroscience to demonstrate that belief in supernatural reward and punishment was not merely a quirk of Judeo-Christian culture, but ubiquitous in human nature, and with ‘pro-social’ results.

Fear

As he wrote: ‘This is not random, but a systematic belief which is very tightly associated with following social norms, including not breaking taboos, co-operating, and denying selfish behaviour… it turns out that people primed particularly with concepts of supernatural punishment will co-operate more.’

Two other academics, a few years earlier, in a paper entitled Divergent Effects of Beliefs in Heaven and Hell on National Crime Rates, emphasised the crucial point not just that eternal damnation was quite some disincentive, but it was necessary for the invigilator to be supernatural as that meant no crime would be unobserved.

Triple murderer and convicted rapist Kyle Clifford was given three whole life orders

This is not something which could ever be achieved by even the most efficient of secular justice systems, with millions of CCTV cameras.

Or as they wrote: ‘Unlike humans, divine punishers can be omniscient, omnipotent, infallible and untouchable – and therefore able to deter transgressors who may for whatever reason be undeterred by earthly policing systems.’

Their analysis, strikingly, was that there was a ‘strong negative effect of rates of belief in Hell on crime, and a strong positive effect of rates of belief in Heaven on crime’.

In plain English: without the prospect of Hell for the wicked, the idea of an all-forgiving God is actually more likely to make people commit crimes.

The analogy with the behaviour of a child whose parents always praise but never punish is all too obvious.

Their point about the all-seeing and punitive deity is even more relevant to the UK today, where detection rates are pitifully low. Little more than 4 per cent of burglaries and only 2 per cent of vehicle thefts result in a charge.

And even for the tiny minority successfully prosecuted, the punishment is paltry, including for the most prolific offenders.

Last week the Mail published examples of this, including that of a criminal called Ross Philippart, who had 33 previous theft convictions: after his latest spree, while on bail, which included swiping a charity box for military veterans, he received a sentence of just six months (of which only half would be served in prison).

And analysis produced last week by the campaign group Crush Crime, suggest that of an estimated 13million crimes committed in the year to

September 2024, just 71,573 jail sentences were handed down by judges or magistrates, which implies that as few as one in 200 offences results in a custodial sentence.

Punish

In this context, it would hardly be surprising if the disappearance of a belief in an all-seeing deity capable of meting out eternal punishment has led to a sense of impunity among the criminally-inclined.

I understand why the preachers of today prefer to emphasise only the God of Forgiveness rather than of Vengeance: that is deemed to be very, well, Old Testament.

But the New Testament has numerous references to Jesus (who was of course a Jew) warning of the prospect of what he called ‘Gehenna’ – a fiery place of divine punishment in Jewish law. For example, in Luke 12.5: ‘Fear the One who… has authority to cast into Gehenna; yes, I tell you, fear Him.’

This is now regarded as uncivilised, even barbaric. But the consequences of a loss of belief in divine punishment have been, in their own way, profoundly destructive of civil order – something governments of different political complexions seem unable to reverse, to the great anger of their electors. Or at least the law-abiding ones.

John Hunt was doubtless not thinking of all this when he invoked Hell in his shattering remarks at Kyle Clifford’s sentencing last week (which the killer refused to attend).

But he certainly made me think.